South Korean man fights for father, 50 years after North Korea hijack

Half a century ago a North Korean agent hijacked the flight carrying Hwang In-cheol's father.

Pyongyang never returned him, and the search has defined his son's life.

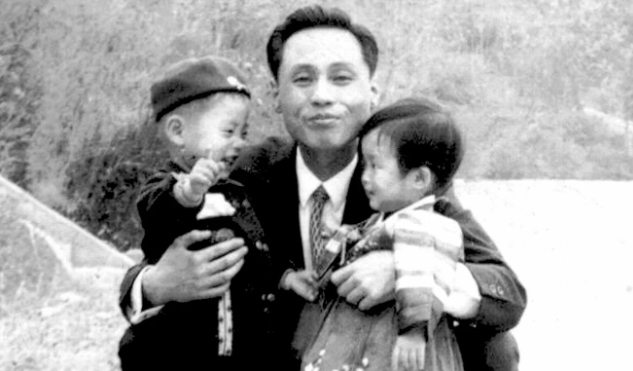

Hwang was just two when he last saw his father and knows him only through photographs, but he has spent much of his adult life campaigning for him.

A producer for South Korean broadcaster MBC, Hwang Won was starting a business trip on a domestic Korean Air flight from Gangneung to Seoul's Gimpo airport on December 11, 1969.

Minutes after take-off North Korean agent Cho Chang Hee slipped into the cockpit and diverted the plane to Pyongyang at gunpoint.

Survivors say three North Korean fighter jets escorted it in to land, and that Cho was met by army officers and driven away.

The 50 passengers and crew were blindfolded with handkerchiefs before they were taken off the plane.

The incident sparked international outcry, prompting a UN resolution denouncing the hijacking, and two months later 39 of those on board were repatriated, but Hwang's father was not among them.

Returning passengers said Hwang Won had been dragged away after resisting efforts to indoctrinate him and questioning the North's ideology.

The Red Cross has long demanded the return of the remaining 11 South Korean, but Pyongyang has repeatedly denied abducting them, claiming some had chosen to stay.

Their plight soon dropped from public attention, but the impact on Hwang's family has never faded. "My life has been a cycle of misery," said his son.

His mother was left traumatised by her husband's disappearance while doing something as ordinary as taking a plane, and she was consumed by "fears over minor things", said Hwang In-cheol.

She would stop her children riding bicycles to avoid the risk they could be hit by a car, or going swimming in case they drowned.

Later in life, his father's detention in Kim Il-sung's Communist North was "a major handicap" as he would stumble on background checks when applying for decent jobs because his father was in Pyongyang.

In 2001, at one of the government-arranged reunions periodically allowed by Pyongyang for families separated by the Korean war, one of the flight attendants, Sung Kyung-hee, met her mother for the first time in more than 30 years.

The sight of the pair's tearful reunion inspired him to embark on a search for his father, quitting his job at a publishing company to travel across the South to raise awareness about the incident.

"I started out with the simple thought that I should meet my father too," Hwang said.

He would now be 82, but he is sure he was still alive as recently as 2017, when an intermediary gave him answers to questions that only his father would know.

After some research, Hwang seized on the United Nations' Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft, ratified by the North in 1983.

"Since the crew members and passengers have not arrived at their final destination, the plane is still in flight according to the treaty," he said.

Seoul could demand the North abide by the international agreement and free the abductees, Hwang said - but his pleas for government action have gone unanswered.

Initially Seoul had encouraged the hijacking victims' families to keep a low profile, saying their actions could complicate their relatives' lives in the North.

Inter-Korean relations have gone from warm to cold and back again in his years of campaigning, but the diplomatic process has made no difference to his quest.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in met three times with the North's leader Kim Jong-un last year, but Hwang remained a bitter onlooker.

"It was just an extension of the empty calls for reunification that I'd heard during the previous liberal administrations," Hwang said.

"Humanitarian issues - by far the most important - have always been left out. The ignorance and indifference of the South Korean government has turned into a huge pain for me."

At the UN's Universal Periodic Review of human rights in North Korea in May, Iceland and Uruguay specifically demanded Pyongyang release the remaining hijacking victims, but Seoul only asked it to "address the issues of abductees and prisoners of war".

The South's unification ministry - which handles cross-border affairs - declined to comment on whether the hijack victims were discussed during last year's summits.

Hwang begins his days at 4am to look for odd jobs on construction sites.

After he finishes work around 5pm, he devotes his evenings to writing press releases and giving media interviews.

He admits he sees no end in sight, but adds: "If I give up, I will just become another perpetrator forcibly detaining my father".

And he still lives in hope. "I have no interest in seeing my father's dead body or to weep at his grave," Hwang said.

"All I want to do is to check how much I resemble him and to feel what it's like to have a father."