MapleStory, Neopets and Warcraft: Can your childhood games recapture the magic?

SINGAPORE — For those who grew up as the internet entered the mainstream, their memories of that era are intertwined with a handful of iconic video games.

For Wesley Teo, 24, those games were MapleStory and Club Penguin, two massively multiplayer online games (MMOs) launched in the early 2000s.

"I remember pretending to be sick in primary school and requesting to leave school early, just so I could play a Club Penguin seasonal event," he says.

"When I finally got home, I realised that the event's start date was in US time and it would be out only the next day. I was so heartbroken."

These moments are among the fondest memories of his primary school days. Teo says: "I found my close friends in school through these games. We would always gather to share what we did with our characters."

MapleStory (2003) is a South Korean side-scrolling fantasy adventure game known for its colourful 2D graphics, while Club Penguin (2005) let users play as cartoon penguin avatars in an Antarctic-themed virtual world.

However, Club Penguin was discontinued in 2017 and lives on only through fans' unofficial private servers.

Today, it is part of the digital ephemera that constitutes that early phase of the internet, alongside other games popular with Singaporeans that have become largely inactive — such as Gunbound (2002), Ragnarok Online (2002) and Audition Online (2004).

Imtiaj Alom, a 31-year-old civil servant, says: "I remember staying up late trying to master the Boomer tank in Gunbound. I used to switch off my room light and mute my PC so my parents wouldn't realise I was staying up playing video games.

"These games used to be such a big part of my life, and so many of them have faded away. Thinking about it today makes me realise how temporary all of this digital stuff can be."

Yet, not all games from that era have disappeared.

MapleStory celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2023, while World Of Warcraft (2004) and Neopets (1999) are celebrating their 20th and 25th anniversaries, respectively, in 2024.

Although the peaks of their player bases are behind them, these games remain big businesses.

The MapleStory franchise has earned over US$5 billion (S$6.6 billion) in lifetime revenue for South Korean publisher Nexon, with the flagship game achieving record full-year revenue in 2023.

As of 2024, World Of Warcraft has over seven million subscribers, with a monthly subscription to the game starting at $17.50 a month.

Part of what has kept these games alive is how they tap one's nostalgia for a bygone era of the internet.

This has driven a slew of fan-run private servers, which offer a time capsule-like re-creation of the games as they existed in the 2000s.

Cashing in on this sentiment, developers have introduced classic game modes and re-releases aimed at recapturing the original magic.

Nexon released MapleStory Worlds in North America in 2024, which was previously available only in South Korea. The feature allows players to create custom worlds using the game's 2D graphics, including those reminiscent of the game's early years.

Meanwhile, World Of Warcraft Classic, launched in 2019, allows players to experience the fantasy role-playing game as it was in its early days, warts and all.

Clayton Stone, associate production director of World Of Warcraft Classic, says the Classic version was created by a small team of developers in response to passionate players' demands to revisit the game's early years.

Despite the technical hurdles of rebuilding the 2000s game with modern code, the overwhelmingly positive reception from fans validated the team's efforts, and led to the development of more experimental and nostalgia-driven modes.

"Nostalgia evokes powerful emotions and memories, drawing players back to games they loved in the past. I think the success of World Of Warcraft Classic underscores this," says Stone.

"Sometimes, a way to ensure a game's enduring legacy is to return to where it all began and remind players what it is that made them fall in love in the first place."

Some games, like fantasy MMO RuneScape, see nostalgia as a way to begin anew. Old School RuneScape, which began as a re-creation of the 2007 version of the game, uses player polls to determine what kinds of new features should be introduced to the game.

These range from small details like the names of bosses to what content the developers should prioritise working on next.

This faithfulness to the original and the emphasis on player agency paid off, with Old School RuneScape's concurrent player count surpassing that of its more modern iteration in 2023.

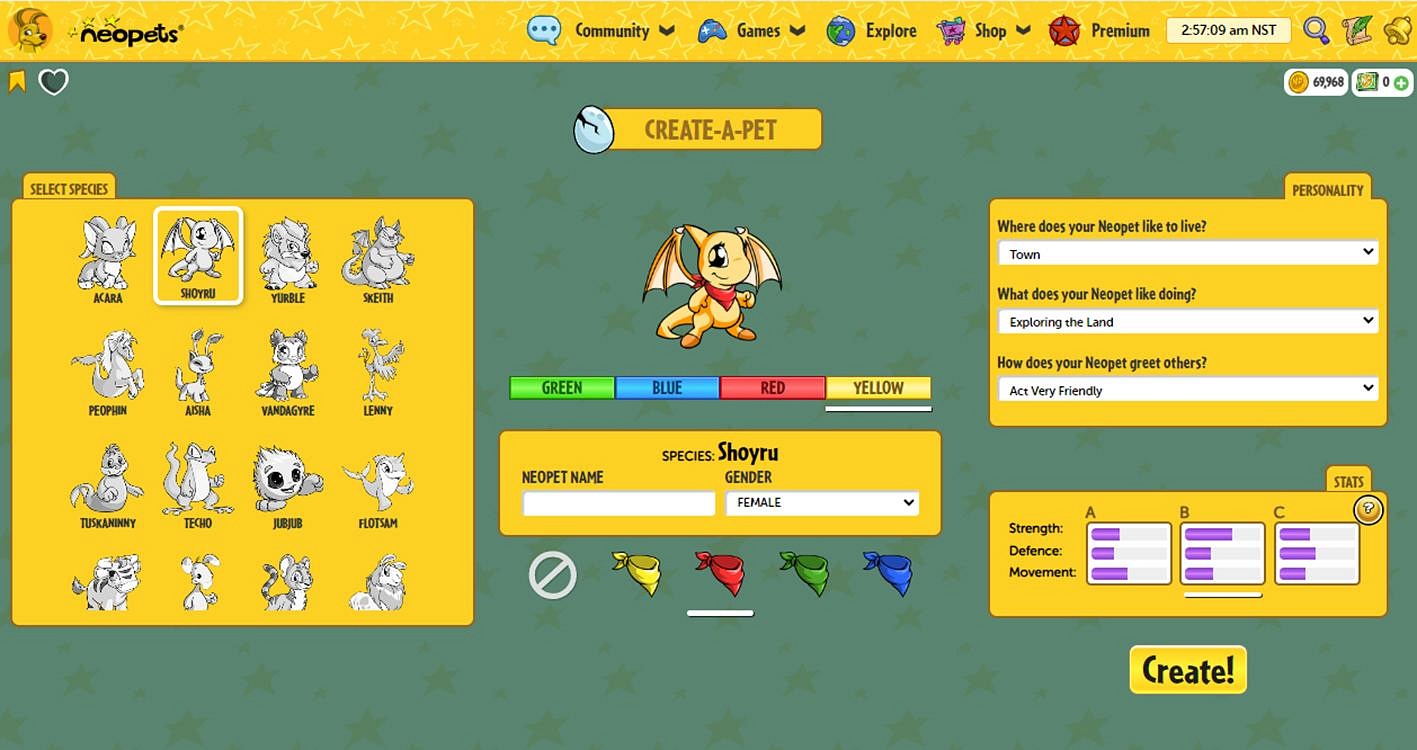

Similarly, the developers of virtual pet game Neopets are seizing on nostalgic appeal to breathe new life into their game, which has accumulated over 150 million total users in its lifetime.

Dominic Law, the game's chief executive, says monthly active users plummeted to around 100,000 players in the 2010s, a time when few changes were made to the game.

Following a management buyout in 2023, this number has risen to around 300,000 monthly active users.

Law, who is based in Hong Kong, attributes this rise to his team restoring features of the game which had fallen apart — such as the discontinuation of support for the website's Flash games.

For him, Neopets holds a special place in preserving the history of the internet. "We protected and kept the early internet culture in its purest form," he says. "Neopets captures this early internet culture that's not seen elsewhere. A lot of people treat this IP as a way to revisit a very serene part of what the internet was about."

The Neopets team now sees its future in bringing back "relapsed" players by making it easier to recover dormant accounts.

In the lead-up to the game's 25th anniversary in November, it has introduced a new storyline which reframes the platform's decline as an in-game event draining all the colour from the fictional world of Neopia — in a bid to re-engage old players.

But can these efforts truly recapture the magic?

Most of the gamers who spoke to The Straits Times expressed mixed feelings about returning to their favourite games.

For university administration worker Serynn Guay, 39, a defining game of her formative years was Neopets, which she played in a time when it felt like everyone in her school had a virtual pet in Neopia. The game allows users to create and care for virtual pets in an online ecosystem of forums, markets and battles.

"There was no social media or smartphones, so whatever your community was into felt like your whole world," she says.

She believes that such human connections are the game's "magic" — something that is hard to recapture when playing as an adult.

This social aspect often extends beyond the virtual world. Lenon Ong, 28, an intellectual property lawyer, says one of his most memorable experiences with MapleStory was dating someone virtually through the game.

While in-game communities and markets were common among games of that era, MapleStory stood out for allowing couple rings and in-game marriages - which resulted in several widely reported real-world marriages in Singapore.

Though he later met his virtual date in real life, Ong says they decided they were better off as friends.

But his continued interest in the game means he still attends gala dinners celebrating the fan community organised by MapleStory's South-east Asia distributor, PlayPark.

Beyond these games' sense of community, there is also the wonder that can be hard to rediscover because of how drastically the internet has changed since the 2000s.

MapleStory fan Gabriel Low, 30, says there is a certain "je ne sais quoi" — French for an indescribable quality — that came with playing online games then.

"Data-mining was less sophisticated back then and gamers could not get a complete view of the game's inner workings with a simple web search," he says.

Updates to MapleStory and World Of Warcraft today — as well as those for newer MMOs like Destiny (2014) and New World (2021) — are sometimes data-mined upon release, with large swathes of their secrets put online on convenient wiki pages.

Data-mining is the process of extracting information from a game's code to uncover hidden or unreleased content.

In contrast, rumours in the 2000s could not be easily disproved. Information could often be found only by interacting with other players or venturing into the unknown.

Low, a Microsoft recruiter, adds: "Gaming was 'slower', but exploring the game world to discover hidden secrets was exciting.

"I think the younger generation is more accustomed to faster-paced games with better graphics. It is seeking a different experience."

The elements that made 2000s games memorable — inconvenient mechanics, unintuitive design and time-consuming quests — now seem out of place compared with those of modern games.

The early 2000s were a wild west of buggy design that gave rise to some of gaming history's most unforgettable moments.

In 2005, World Of Warcraft made headlines with its "Corrupted Blood incident", when a programming oversight led to an in-game pandemic that spread across the fictional world of Azeroth.

Players became disease carriers, while non-player characters acted as asymptomatic spreaders. The incident caused widespread panic within the game for several days, as players sought to avoid infection while major hubs became choked with player corpses.

In 2006, RuneScape had a historic bug known as the Falador Massacre that allowed players to attack one another in designated safe zones, leading to a player-on-player bloodbath.

Not all quirks led to massive events. For many, the consequences were deeply personal, in a time when scams and exploits were more commonplace.

Mobile game developer Marcus Lim, 32, says one of his most memorable gaming experiences came when he was playing RuneScape in his primary school years.

New to the game, he was battling monsters when a higher-level player approached him, offering a set of adamantium armour if he was willing to use the in-game follow function.

"I foolishly agreed," he recounts. "I followed him deeper into the dungeon, taking lots of damage from strong monsters. I got worried and tried to unfollow him, but I couldn't click his character properly to do so.

"I quickly ran out of food and died, dropping all but my top three most expensive items for the scammer to pick up. I was devastated, but I learnt an important lesson that day about blindly trusting internet strangers."

Beyond better graphics, modern online games have introduced features — such as making in-game travel faster, decreasing difficulty and streamlining quests — that have changed gaming.

Jarieul Wong, 40, says: "I remember spending 12 hours on World Of Warcraft killing the same enemies over and over again, just for the small chance that they would drop a rare item."

"I think modern versions of the games I played give players a greater sense of accomplishment and achievement without investing that much time and effort," adds the public relations agency co-founder.

He recalls living and breathing the game during his army days, when he and his army mates would spend bookout weekends pulling all-nighters questing in Azeroth.

"It was crazy that we had such stamina. Even now, when I return to World Of Warcraft, I get flashbacks to my army days and the camaraderie of hanging out with friends virtually."

Not everyone finds the old inconveniences daunting. For Dan Tang, 39, co-founder of an edtech company, the messiness and mystery of these early games were what made them memorable.

"No one knew what they were doing, so people built communities and shared discoveries - compared with today, when everything is just data-mined before release," he says.

Tang returned to World Of Warcraft through its Classic mode during the Covid-19 pandemic and appreciates how it preserved the original game's challenges. These include "mobs" of enemies and quests so difficult that players had to team up to beat them.

This was a common experience among gamers who spoke to ST, who say that as their games have evolved, new anti-frustration features have made their worlds more accessible, but less social.

Teo notes that modern MapleStory has more content that can be experienced alone. "Grinding has never been easier. You can solo (take on alone) the majority of bosses, compared with the past where you needed to recruit a party," he says.

This comes with the territory of an ageing player base. Adults have less time to spend on their favourite games, and less patience for features they find frustrating or time-consuming.

For Stephanie Gan, 39, revisiting the games of yesteryear was bittersweet.

The public relations professional recalls how she and her friends would strategise to take down bosses in MapleStory's party quests.

"My level was usually lower than my friends', so I often played the mage to heal them as we took on bosses. I had fun just hanging onto ropes or running for dear life when enemies got too close," she says. In the early years of MapleStory, mages were the only player class capable of healing others.

She says revisiting the game 15 years later was less satisfying because she no longer sees herself as part of the cultural zeitgeist these games are trying to exist in today.

"Times have changed - so do the games and their generations. The younger generations are into PUBG, Minecraft or Roblox, which I've tried but don't appeal to me as much."

Fellow gamer Yong Qing Ru, a 26-year-old IT professional, also revisited MapleStory recently and found it "different and foreign".

"But when I revisited those older areas in MapleStory I used to hunt in as a kid, I feel nostalgic thinking about the sweat and tears that went into levelling up," he says.

"It's not so much about missing the old game, but more about missing the memories of playing them as a child."

Although video game design has marched on, modern play traces back to these early roots.

Games like World Of Warcraft made features like "daily quests" mainstream, while the likes of MapleStory and Neopets popularised virtual pets and "gacha" mechanics, a mystery loot box system that has come under fire for its similarities to gambling.

Yet, despite their importance in cultural history, games are more easily lost to time than other media.

A 2023 study from the non-profit Video Game History Foundation found that 87 per cent of classic video games released in the United States are critically endangered — meaning they are no longer commercially available.

"For comparison, this is slightly above the availability of pre-World War II audio recordings (10 per cent or less) and slightly below the survival rate of American silent films (14 per cent)," wrote study author Phil Salvador, referring to games from the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s.

In copyright law, video games are treated differently from books, music and other media. Strict restrictions, such as the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act, lack the exemptions that allow archives and private groups to preserve video games in the same way.

Players who recreate their favourite games on private servers tell ST that it is understood that hosting such servers is illegal, and that these could vanish overnight if the copyright holder wills it.

For many who see online games as a source of community, their digital memories survive only as long as doing so is profitable for developers.

Teo started playing MapleStory again in 2023 through an unofficial private server that emulates the game prior to a major and divisive update known as the "Big Bang" that was rolled out in 2010.

For him, being able to "lepak in free market" (hang out in the game's central community hub) recaptured some of the original childhood joy of playing the game.

Still, he says going back to these servers can recapture only so much of the lost wonder because the player base can never match the hordes the game used to command. And, he adds, those who still play it are likely to be super-fans more focused on optimal gameplay than socialising.

"If you're unable to find such a community, the experience of playing these games can be lonely, like walking through your primary school that's going to be demolished soon."

This article was first published in The Straits Times. Permission required for reproduction.