A bug's life: A sneak peek at sustainable cricket farming in Singapore

They say there's no rest for the wicked.

But judging by the way urban farmer and author Christopher Leow has been flitting from one green project to the next, neither is there rest for the superhero — in this case, Singapore's "Captain Planet", who's been hard at work the past year doing (among other agricultural and agri-educational tasks) R&D on sustainable cricket farming.

The 36-year-old CEO and co-founder of Future Protein Solutions takes us on a tour of his cosy facility located within the grounds of Gallop Kranji Farm Resort at 10 New Tiew Lane 2, to give us a closer look at this form of "micro livestock", and how the resource-efficient system he has set up could be a viable and sustainable solution for local and regional farmers alike.

Yeah, crickets or insects in general have been consumed in humans' diets since we were hunter-gatherers, so it's not uncommon. In Thailand, you often see it as a street snack. Recently, we've been looking at insects as a potential alternative protein source, and realised that the resource efficiency is really amazing.

Crickets are cold-blooded, so they don't need to heat themselves. Therefore, in a tropical climate, they require much less energy or calories than, say, a cow. That factor allows the farmer to use less feed, less water, less space to rear these crickets.

The moment they hatch, we start feeding them a mixture of dry feed (that we take from food manufacturing by-products like soya bean pulp) and organic vegetables that we grow without any chemicals, using cricket manure (also called "frass") as fertiliser. It takes anywhere from 30 to 60 days for a newly hatched cricket to reach maturity.

And you know that cricket chirping sound? That is when they are mature and ready to mate. We use a coconut-fibre substrate to let them lay their eggs, which take seven to 10 days to hatch, and then the cycle continues.

The more we are able to replace current, more resource-intensive stuff with crickets, that would be how we will transit away from a very resource-intensive model. The amount of resources required is very similar to what's currently trending, like plant-based foods or cultured meats.

At our farm, we also try to be as green as possible. At this facility, we are fully on solar, so we don't consume any other external energy from the grid, and we also have a rainwater harvesting system. We're trying to build that culture from the internal team, and in everything that we do.

A lot of the farming processes that are being used right now, mostly in countries like Thailand and Vietnam, are very labour-intensive. So we needed to think of ways to reduce the labour required in a high-cost country like Singapore.

We worked with a start-up to develop and create this automatic feeder from scratch. It's a robotic feeder that will dispense the feed for the crickets, and you can also attach sensors to it like cameras. Eventually, it will use machine learning to dispense the feed automatically without any human input.

At the same time, the auto feeder is also modular — you can attach temperature and humidity sensors, and sensors to monitor cricket growth, so that we can create optimal grain conditions for the crickets, and start studying them and figuring out how to make them more comfortable, and grow faster and better.

After the crickets have reached maturity, we process them into a final product. The first step is to euthanise them. We put them in a freezer, and since they're cold-blooded, they just sleep and don't wake up.

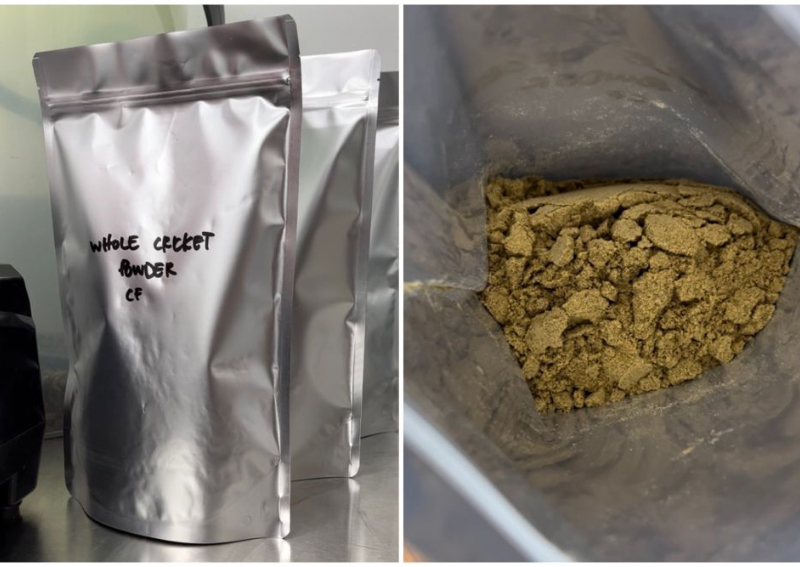

After that, we take them out, wash them, dry them, and roast them. Then, we remove the oil (which can also be used for culinary applications), so that we are able to grind it or mill it to a much drier and finer quality.

People prefer to have it in a powder form, especially in countries that are not familiar with crickets. When they don't see the crickets, then it's more acceptable to them!

There are two different tracks that we are looking towards. One is developing the systems — for example, the growing system, the auto feeder — that we can then use to help other farmers produce crickets more effectively. Hopefully, other farmers in Singapore can try growing crickets.

The other thing we're exploring is working towards functional ingredients, which means, after we get the cricket powder, we can extract further special components from there, like omega acids (crickets have more Omega-6 acids than salmon, actually), iron, calcium. Just imagine, we could get supplements from crickets in the future.

The dream is really to be able to produce crickets at scale in a cost-efficient manner, by allowing us to control different inputs for different products.

For different kind of products, you need different flavours. For snacks, you want it to be very savoury, so if you feed them fish meal, they will taste more seafood-y. If you're doing something like a sweet application, like a protein bar or a protein shake, you want it to have a milder flavour. You might want to harvest them at different stages as well.

All these little nuances are what the farmer needs to be able to control for different scenarios and different clients.

ALSO READ: 'Granary of China' braces for more wheat-damaging rain

This article was first published in Wonderwall.sg.