What's it like to get life-changing surgery that literally changes your face

Just over a year ago, I had a life-altering surgery. The lower half of my face was broken apart and put back together, relieving me of chronic pain.

When half your face changes, it feels like losing part of who you are. I didn’t tell many friends about my surgery – the majority of them will find out via this story – and when I see them in public, they don’t recognise me. For a while, I didn’t recognise me either. I spent months reconciling the relationship between my mental and physical selves and I’m finally at a point where I feel at home in my body.

In the spring of 2020, I started having soreness in my jaw that got increasingly worse. At first I attributed it to grinding my teeth at night, a result of the stress I was experiencing at work, but by July, the pain had gotten so bad that I had trouble chewing. I went to an orthodontist who took x-rays and realized that my jaw was misaligned..

The pain stemmed from friction in my joints; joints are supposed to be curved, but the rubbing had caused mine to be flat. I was referred to a clinic that specialises in jaw surgery, and that’s where my story began.

When I learned that I needed orthognathic surgery, I was calm – relieved even, and happy to know that a solution beyond long-term pain medication existed. The doctor would perform a Bi-Maxillary Osteotomy, a fancy term for double jaw surgery, breaking the top and bottom jaws before shifting and securing them with screws. I knew my face would change, but he told me it wouldn’t be too drastic.

According to my doctor, people would know I’d done something to my face, but they wouldn’t be able to figure out what part I had changed. I understood that this would be physically taxing, but because I had accepted that my face would be different, I didn’t think it would affect my mental state or permeate all other aspects of my life.

I typically process major life moments with my psychologist, but I was uncharacteristically calm about this one. At the time, it was just another medical procedure.

The weeks between my diagnosis and surgery were a frenzy of tests, x-rays, check-ups and renderings of what my new face would look like. The renderings showed where my bones would be shifted to, but it was difficult to imagine how the structural change would translate into facial features. I was nervous about the aesthetic outcome, but years of therapy taught me to reframe logically before I started catastrophising.

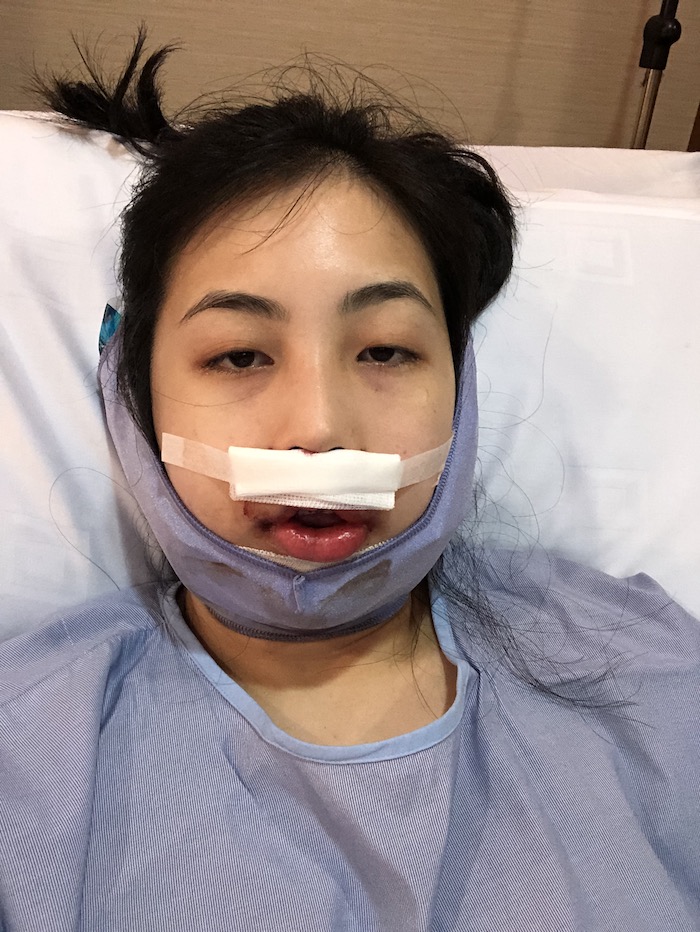

Considering that my bones were misaligned now and would be shifted to their optimal positioning, from a rational point of view, I should come out feeling better. Things felt surreal until the nurses wheeled me into the operating theatre. I woke up hours later, disoriented and extremely nauseous. When a team of nurses transferred me to a different bed, I tried to scream in pain, but realized that my mouth couldn’t open more than a centimeter.

It wasn’t wired shut, my face was just so swollen that I was physically incapable of moving it. I immediately panicked – how would I ask for help or tell people that I was in pain if I couldn’t talk? I thought I was the only one crying, but later discovered that my mother had also started crying at the sight of my swollen face, blood draining from tubes into cups dangling from the sides of my mouth.

I spent two sleepless nights in the hospital watching Grey’s Anatomy (the show seemed like it fit the vibes) and asking the nurses when I could leave. I couldn’t use the bathroom myself so I had a catheter inserted and I was labelled a high fall risk so I slept on a motion pad that detected my movements and would sound an alarm if I moved too much. I was fed through a drip tube and given sponge baths in bed.

When my doctor checked on me, he told me the surgery went beautifully, but when I looked into a mirror, all I could see was a swollen face the size of a melon. I was terrified of what was waiting for me beneath the swelling. What if I hated it? There was no turning back now. Reversing the surgery meant reverting to my misaligned jaws, and no sane doctor would agree to that.

Once discharged, my parents were my main caregivers. My mother slept beside me for a month in case I woke up in pain, and she accompanied me to every doctor appointment. My dad came home early from work to grind up my pills and make milo before bed.

They created a schedule for my medication, and took turns feeding me through syringes because I still couldn’t open my mouth. For the first few weeks, I had a mix of nutritional supplement drinks and berry smoothies – both of which I still gag at the thought of.

I was so desperate for the taste of savoury foods that I was elated when I progressed to soft non-chew foods. Mashed potatoes, blended cereal, and watery congee were all on rotation and consumed with a baby spoon.

I had grand plans for my 30 days of hospitalisation leave. I had a list of books and TV shows I wanted to finish, stories that I wanted to write and dresses that I wanted to sew. I did absolutely none of them.

My eyes hurt when looking at screens, I got nauseous watching TV, and I was too tired to hold a book up, much less design, measure, cut and sew fabrics. I slept most for most of those 30 days, only leaving the house to go to the doctor or for 15 minute walks around my block.

The first 30 days after the surgery is a time to recuperate, but I wasn’t sure which part of my body was more in shock: the physical or mental. The swell reduction progress messed with my mind; there were times when the sides of my face would swell unevenly, or healing would plateau and I would feel discouraged.

According to my doctor, “Swelling typically subsides more quickly during the first and second postoperative week. Studies have shown that approximately 50% or more of the swelling would have resolved by the end of the third week,” however, “the rest of the residual swelling subsides more slowly over the next few months.”

All the Reddit forums I had perused and all the jaw surgery vlogs I watched didn’t prepare me for the mental hit I would have to recover from. I hadn’t realized how closely my identity was tied to my physical appearance. I desperately needed to talk to my psychologist, but frankly, I was too tired and the warbled mumbling I could muster was difficult to understand.

In the following months I struggled to reconcile the difference between my old and new face and spent many hours crying to my psychologist, parents and friends. These feelings of alienation and estrangement to my body were heavily discussed in therapy.

After one of my initial sessions back, my psychologist followed up with an email that read, “Be patient with the internal/psychological discomfort – old or new, good or bad, familiar or strange, all of it is Claire.” For the first time, I was reminded that even though my exterior had changed, I was still the same person inside.

When it was time to venture outside, I was nervous because I didn’t want people to ask about my face – I just wasn’t ready to talk about it. Wearing a mask helped to an extent – people recognised the top half of my face. In other instances I would be sitting in a restaurant sans-mask and my friends wouldn’t recognise me at all.

Despite my parents preparing the extended family, my relatives were still shocked when they saw me; a family member introduced herself in-person because she didn’t know who I was. I got many well-intentioned comments from relatives and friends ranging from, “you lost so much weight, you look much better now” to “your new face is much prettier” and even “your face looks fat, did you gain weight?”

But these were ill-received because they were comparisons that focused solely on my looks, and not on the fact that I had been relieved of my chronic pain. I was overwhelmed by the comments and angry too, but my parents reminded me that people often struggle to say the right thing when they encounter an unfamiliar situation – or in my case, an unfamiliar face.

I didn’t have the capacity to extend my parents’ grace and started declining invites to social and family gatherings instead. I was desperate for someone to say something uplifting and when I needed it the most, I received this text from my friend Vivian:

“Hey babe because you mentioned some ppl said you looked different, just wanted to tell you that even if people say you look different after the operation (hello I could recognise you in an instant at Raffles City), I still think you’re beautiful and I dare say you look even better too! And most importantly your jaw is now healthy and not hurting you anymore right!!”

I realised that because everyone else had been putting the aesthetic result first, I had begun to as well. I had completely lost sight of the main reason that I needed the surgery in the first place. I started adopting a more neutral perspective towards my surgery, as per my psychologist’s advice.

I stopped labelling the result as “good” or “bad” and simply acknowledged it for what it was – a change. It would take a while to feel comfortable with the change, but in the meantime I could focus on remembering other facets of myself.

By January, the unsolicited comments, still-swollen face and lack of exercise had taken a toll on my self-esteem. I deleted social media for a period because I kept spiralling into a rabbit hole of comparison. Gaining my confidence back took awhile.

First, I learned how to move my facial muscles again. I would sit in front of a mirror practicing smiles, frowns and other forms of emoting. Next, I had to come out of hiding – it was time to post a picture on Instagram. The perks of being in the creative industry means I have many talented friends.

Kayle (@yskayle), a photographer, and Eileen (@mkbyeileen), a makeup artist, offered to do a photoshoot and proceeded to set up a makeshift studio in my HDB lift lobby. Eshton (@eshton), a photographer who also happens to be my cousin, pushed me to get back into the dating world and took photos to update my profile for when I was ready.

All the recovery time allowed for ample self-reflection. I realised that pre-surgery, I’d been coasting and allowing life to happen rather than taking more intentional steps towards the kind of life I wanted; it was time for a change.

I extended this new attitude towards all my relationships – romantic and otherwise. I stopped hanging out with people that left me feeling empty inside, and made more of an effort with truer and fewer friends.

Venturing back into the dating world was anxiety-inducing, but I kept reminding myself that anyone who wouldn’t be interested just because my face was a bit swollen, or was weirded out that I looked very different mere months ago, wasn’t worth my time.

Shortly after diving back in, I met my current partner. He was curious about my surgery, but not fazed by all its gory details, and he didn’t care that I dribbled on our first date due to my lower face still being partially numb.

I recently asked my doctor how people usually feel about their new faces, he told me that “People react favourably after receiving jaw surgeries as their jaw discrepancies are corrected resulting in better function and aesthetics.” Essentially, people look better and feel better – what’s not to love? It’s been 13 months since my surgery and I’m physically and emotionally in the clear.

It’s easy to say that I would do it again, but if you had asked me three-four months after surgery, I would have said no, the trauma was not worth it. The pain, nausea, general post-surgery side effects and dealing with a new face completely obstructed the light at the end of the tunnel that everyone kept telling me to see.

Before I got the surgery, my doctor told me that it was life-altering; some people change their haircuts, others change their jobs, and some change their partners. This was meant as a joke, a way to convey the gravity of the situation, but it stirred something within me. While the surgery itself didn’t change my life, it was definitely a catalyst for change.

Altering my face forced me to separate my physical appearance from my personality and dig deep to understand who I was. Putting my fast-paced lifestyle on pause provided me with ample time for reflection and when I recovered, I felt brave enough to take on opportunities and to create my own. In the past year, I permed my hair, got into a relationship and most recently, I changed my job.

Reading about other peoples’ experiences is what eased my mind. If you’re considering this procedure, or you’re just curious about my experience, I’d be happy to answer more (non-medical) questions at @clairedycat19.

I want to thank the wonderful healthcare workers at Mount Elizabeth Orchard. Every single doctor, nurse and hospital staff that I encountered had smiles on their faces, showing genuine empathy for patients despite being on the frontlines of the pandemic for nearly two years.

This article was first published in The Singapore Women's Weekly. Disclaimer: This story was written from a patient’s perspective and recalled experience. All potential errors in medical and technical terms are unintentional.