Are gambling and investing similar?

The Singapore Pools finally reopened its doors on the June 15, 2020, with 4D bets restarted on the June 24, 2020.

This means that we have finally returned to the days where many Singaporeans like my Uncle John (name changed for privacy reasons) can relish in their favourite national past time - queueing up to buy 4D.

The Singapore Pools had only stopped their operations for just over two months, but I am sure it felt much longer than that for many 4D hobbyists. This led me to wonder:

''Why are people so persistent with 4D bets? What is the difference between gambling and investing?''

As someone who has never bought 4D, I wanted to understand how to optimise 4D betting, and if there is any way to diversify 4D bets, just like we should do when we invest.

Despite Uncle John’s attempts to spot 4D number patterns or draw inspiration from birthdays, the generation of 4D numbers are truly random - a draw machine is carefully calibrated to ensure that all numbers have an equal chance of appearing.

Therefore, over the long run, the expected returns should be based on the probability of getting a striking a prize number and the prize money earned.

The winnings and expected outcome for each $1 bet can be calculated based on the table below:

It is easy to assume that placing more bets would increase our probability of winning. Instead of betting $1,000 in a single number, why not spread it across 25 bets, $40 each, or even 500 bets at $2 each?

Perhaps we can even spread it across different 4D draw dates so that we can spot patterns and adjust our strategies accordingly?

Unfortunately, we all know that does not work, because by spreading the bets wider, while you have a greater chance of striking the lottery, your strikes will yield smaller monetary rewards, and hence merely increase your chances of getting the expected outcome , which is to get back $0.659 for every $1 you put in.

Taken to the extreme, if you were to place a dollar bet on every single number, all 10,000 of them, you would get $6,590 back. That’s the best you can do.

In Uncle John’s eyes, I am “gambling” my money in the equities market, regardless of how I do it. There was no certainty in the outcome; at best, I was making an educated guess, based entirely on incomplete information.

The return figures that I share with Uncle John are hardly inspiring. Even if I spread my equities holdings (buying all numbers in 4D), I can only expect 7 per cent to 9 per cent average returns for very diversified fund investments.

These average returns are over a long period of time, something we rarely experience in any given year , with the best and worst years swinging in the range of +40 per cent and -40 per cent.

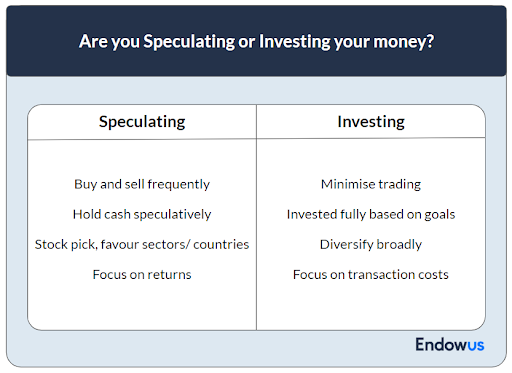

When we are speculating (read: gambling) instead of investing, we are inclined to look at the markets more, and make sporadic trades rather than investing in a consistent manner.

This type of behaviour has been particularly apparent during this Covid-19 crisis, where a study by economists showed that retail investors increased their trading activity by approximately 13.9 per cent for every doubling of Covid-19 cases.

At the end of the day, we have our own personal opinions on whether stocks or index funds are expensive or cheap, which may lead to trading behaviour.

The best we can do is to make an educated guess. We may choose to trade in and out of the market more based on how many educated guesses we have, but the more we indulge ourselves with such thoughts and such behaviour, the more we are speculating, instead of investing.

If I were to look at how systematic my relatives are in terms of their 4D efforts, I could have made a case that their behaviour is closer to investing than speculating! Uncle John dedicated $200 religiously every month on 4D, buying a fixed combination of license plate numbers and birthdays.

Investing should be carried out with the same mindset. We should do our budgeting, know how much we want to invest for our mid- and long-term goals, and invest that money religiously.

We should accept that it is innately difficult to outguess the market and be persistent and consistent (like Uncle John) with depleting our cash holdings so that we put more money at work (also known as dollar-cost averaging).

In contrast, a gambler (market speculator) would be holding on to a huge amount of cash, or in some cases, leveraging up and trying to outsmart the market.

Using the above charts on spreading out 4D bets, it is obvious that while concentrating your money in fewer bets gives you a better chance of a windfall, you also have huge uncertainty in returns.

On the other hand, if you were to take more bets, the variance of outcome narrows, and there is a greater certainty that we get the mathematically expected returns (or loss of 0.341 per $1 put in 4D).

Similarly, spread your investments over countries, sectors, and companies so that you are as diversified as possible, giving you a better chance to capture the growth of the world economy from capitalism.

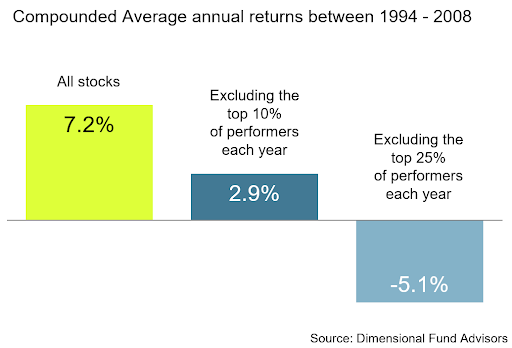

A study done by Dimensional Fund Advisors shows that missing out on the top performers in the global stock market (weighted by market cap, across developed and emerging market) will lead to significantly poorer returns.

By spreading your underlying exposure more thinly, you will have a lower chance of missing out on investments in companies that give higher returns, and hence give you a higher chance of hitting the 7 to 9 per cent historical returns we can get from the equity markets.

Market speculators and gamblers alike tend to focus on potential winnings and outcomes. To them, with the right strategy, right timing, with an element of luck, they would be able to make a bigger earning based on their ingenuity.

However, for market speculators, such an “investment strategy” comes with both explicit (trading and transaction fees) and implicit costs (bid-ask spread, time spent on managing investments and transferring money).

These costs may or may not lead to higher investment returns. If we realise that we are spending more transaction costs than we expect to, then we are likely to be speculating than investing.

This article was first published in Endowus.