Breaking down the costs of development: Is property development unsustainable in Singapore?

There’s a common misconception today that property developers are the cause of higher property prices in Singapore. After all, it seems obvious that developer pricing is the main factor in a condo’s cost. Perhaps that may have been true in the earlier years when developers were making bank with 40 or even 50 per cent margins.

That has all changed today.

In reality though, developer margins are far thinner than most of us imagine; and Covid-19 is putting the screws on an already struggling industry. Here’s what’s happening behind the scenes:

The start point of any condo is the land costs involved. Larger developers, with deeper pockets, can bid for Government Land Sales (GLS) sites. They may also try and buy existing condos up for collective sale.

Smaller developers seldom have the capital to go for GLS sites. They tend to buy up smaller plots, such as plots with three or four older landed properties. This is mainly for boutique developments, which may have 50 or fewer units.

The cost of land can vary significantly, based on factors like centrality, and proximity to MRT stations. For example, one of the most contested land sites recently was Tanah Merah Kechil Link, which was bought at around $930.30 psf.

In other areas, such as the Mount Emily Road site in 2021, prices can be higher. The collective sale of 2,4, and 6 Mount Emily Road this year came to around $1,115 psf. Meanwhile, in Flynn Park, the most recent collective sale in Pasir Panjang, developers paid about $1,355 psf.

As land becomes scarce, prices go up; and along with it, the cost and eventual prices of new launch condos.

A good example of this was in 2017, when Singapore was in the grip of an en-bloc fever.

In that year, we saw a record $1.003 billion bid for a Stirling Road plot, which today is Stirling Residences. The joint bid by Nanshan and Logan, both foreign developers, was $1,057.71 psf. In total, they outbid the second-highest bidder (MCL Land) by $77 million. The eventual land price was 29 per cent higher than the lowest bid price.

While we’re not seeing an influx of foreign developers in 2021, we are poised for another round of en-bloc buying (we explained the reasons in this earlier article).

With seemingly so little land to go around, developers are pressured into more aggressive bids. There is a limit to how much this can be passed on to buyers; so developers ultimately have to accept slimmer margins, whenever the cyclical fight for land begins.

In this sense, developers don’t have the sole power to “set the price”. They’re as much subject to market forces as any of their buyers.

If the en-bloc sale is for a 99-year lease development, the developer will need to top up the lease. The cost is determined by the Singapore Land Authority (SLA). In general, the amount will be based on Bala’s Table, which established leasehold value as a percentage of a freehold counterpart (there’s a longer explanation in this article).

With freehold property, there’s no need to top up the lease; and in theory that shaves off part of the cost for developers. In reality, there’s not much difference. This is because sellers will demand a higher price for their freehold property. In fact, one of the expected benefits to buying freehold is higher sale proceeds in an en-bloc.

The greater the lease decay, the more the developer has to spend to top-up the remaining lease. But if the property is freehold, the developer has to pay more for it. Either way, developers can’t avoid the added cost.

The DC is a tax, payable when the developer gets permission for projects that increase land value. The most typical example would be building a new condo, with an increased plot ratio.

(You can check out this article to learn about plot ratios, which affect how many units can be built, and the height of the condo).

The DC rate is reviewed on the first day of March and September, every year. Although the exact reasoning is seldom disclosed, it’s known that DC rates can go up when the government wants to discourage a supply glut.

In 2018, for instance, when supply was getting dangerously high from en-bloc sales, the government hiked DC rates by 22.8 per cent for residential development.

In 2021, home prices have been rising for six consecutive quarters, and developers are increasingly land-starved. We notice that, along with this, DC rates have been hiked by close to 11 per cent for residential development.

It’s probably not a coincidence that DC rates go up, whenever an en-bloc surge seems likely. Most of the time, if developers are having to bid aggressively for land, it will also happen against a backdrop of rising DC rates.

The following is expressed as a percentage, showing how much each element adds to the selling price:

| Costs | Breakdown |

| Architectural work | 2.5 to 3 per cent |

| Maintenance and Electrical engineering | 0.9 per cent |

| Civil and Structural engineering | 0.85 per cent |

| Interior Design | 1 per cent, inclusive of sales gallery and show flat |

| Landscaping services | 0.6 per cent |

| Inspection by Registered Inspector | Around $3,000 to $5,000 |

| Quantity Surveying | 0.8 per cent |

These are the definite and most predictable costs developers will face. In addition to these, there are some costs that are variable, or optional:

Overall, it’s common for the above to account for about five to eight per cent of the selling price (sometimes as high as 10 per cent).

On top of this, remember the developer needs to have real estate agencies sell the property for them. This can add about three to five per cent to the selling price, in commissions alone.

In total, that makes up around 13 per cent added to the selling price.

This is where things get tricky, as it depends a lot on the contractor and sub-contractors hired by the developer. However, construction costs in Singapore tend to be in the range of $300 to $400 psf, for most condos.

(Luxury condos can cost a lot more than this).

This has also become hazardous during Covid-19, as the cost of manpower and materials can shoot up suddenly. It’s possible for a developer to have set the price and sold the units, but then find that the construction costs are higher than they expect.

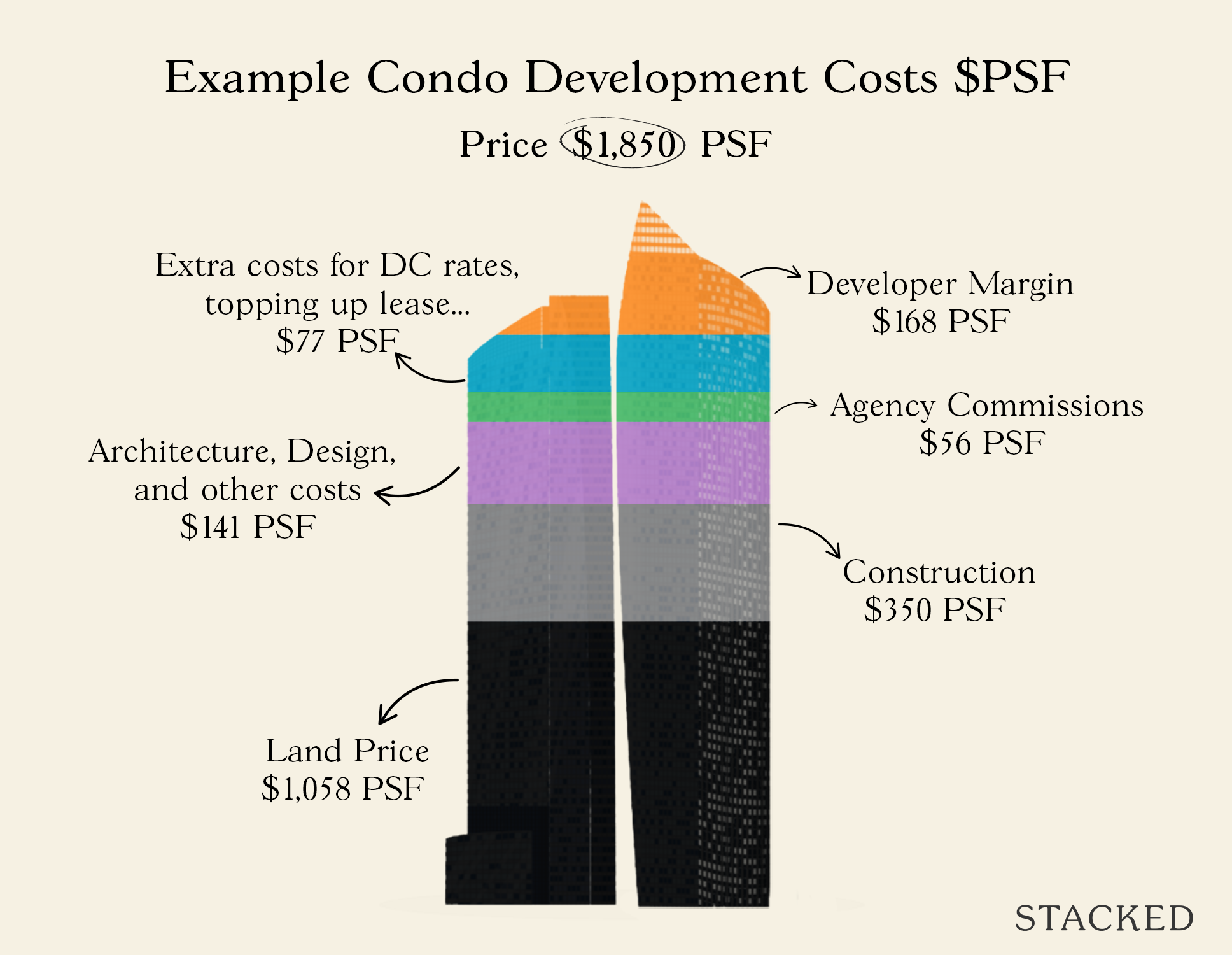

Let’s take a very rough estimate of where margins stand right now.

Say if we take the example of Stirling Residences, for which the base cost is $1,057.71 for the land price. We add an estimated $350 psf for construction costs, coming to around $1,407.71.

Next, we add on 13 per cent, for the elements described above. This raises the price to about $1,590.71.

Bear in mind the actual cost is probably much higher than this, as we haven’t factored in DC rates (we don’t know what they paid), the cost to top up the lease, or the possibility of prices rising due to Covid.

We can see that the median price at Stirling Residences, at the time of launch, was around $1,848 psf.

At a highly conservative building cost of around $1,590.71 psf, this leaves the developer with a margin of just around 14 per cent.

If we were to factor in other costs such as topping up the lease, DC rates, and so forth, it’s more realistic to estimate the margins at being just around 10 per cent. Many business owners might consider this a barely acceptable margin, not especially for the high amount of money that is being invested in each project.

Developers also pay ABSD. They put down 30 per cent of the land price when they make the initial purchase. If they’re able to complete and sell every unit within five years, they can get back 25 per cent of the land price (five per cent is non-remissible).

The ABSD does not take into account development size. A development with 1,000 units has five years, the same as a development with 50 units.

This is the reason why developers are hesitant to buy large plots in en-bloc sales: missing the ABSD deadline could demolish their already thin margins.

The first concern is quality.

When developers work on tight margins and time limits, there’s a greater temptation to compromise on quality. You end up with condos built by the lowest bidder (among sub-contractors), or which are the result of rushed work.

The second issue is the loss of innovation. Developers are less willing to try out new themes or concepts, because of the constraints. This results in a humdrum series of condos, which seem to have little differentiation from one another. It’s been a while since we’ve seen interesting themes, like Savannah Condopark.

We’ve also seen what happens when a developer doesn’t have that constraint (like the recent Jervois Mansion), that display of quality and attention to detail is clear as day to see. Likewise, the fact that it nearly sold out on launch weekend goes to show buyer’s response to that.

The final consideration is size. Smaller units can have a very high price psf, as their overall quantum will still be tolerable. For example, units at The M could sometimes reach up to $3,000 psf, while being quite tiny and having a quantum of under $1 million.

It’s no wonder that our condo units seem to be getting smaller all the time; and this rather unlikeable trend is set to continue, with developers being squeezed.

Something has to give here; and not just with regard to policy. Developers may have become overly dependent on property agencies, which allows them to tack on as much as five per cent to the overall price (see above). We’ll explore this issue in a follow-up article shortly, so do follow us on Stacked for more.

In the meantime, do check out our in-depth reviews of new and resale condos, aimed at helping you make the most informed decision.

This article was first published in Stackedhomes.