How to lower property prices in Singapore: More loan curbs or ABSD?

The Additional Buyers Stamp Duty (ABSD) is seen as a core component of cooling measures. Every time prices creep too high, we see the government ramp up ABSD — most recently on April 27, when the ABSD on foreign buyers was doubled to 60 per cent.

But as we've seen in recent months (although it is probably still too early to judge), the higher ABSD seemingly has done little to dissuade local buyers, and prices are still high. Here's a take on how loan curbs may be the more effective move:

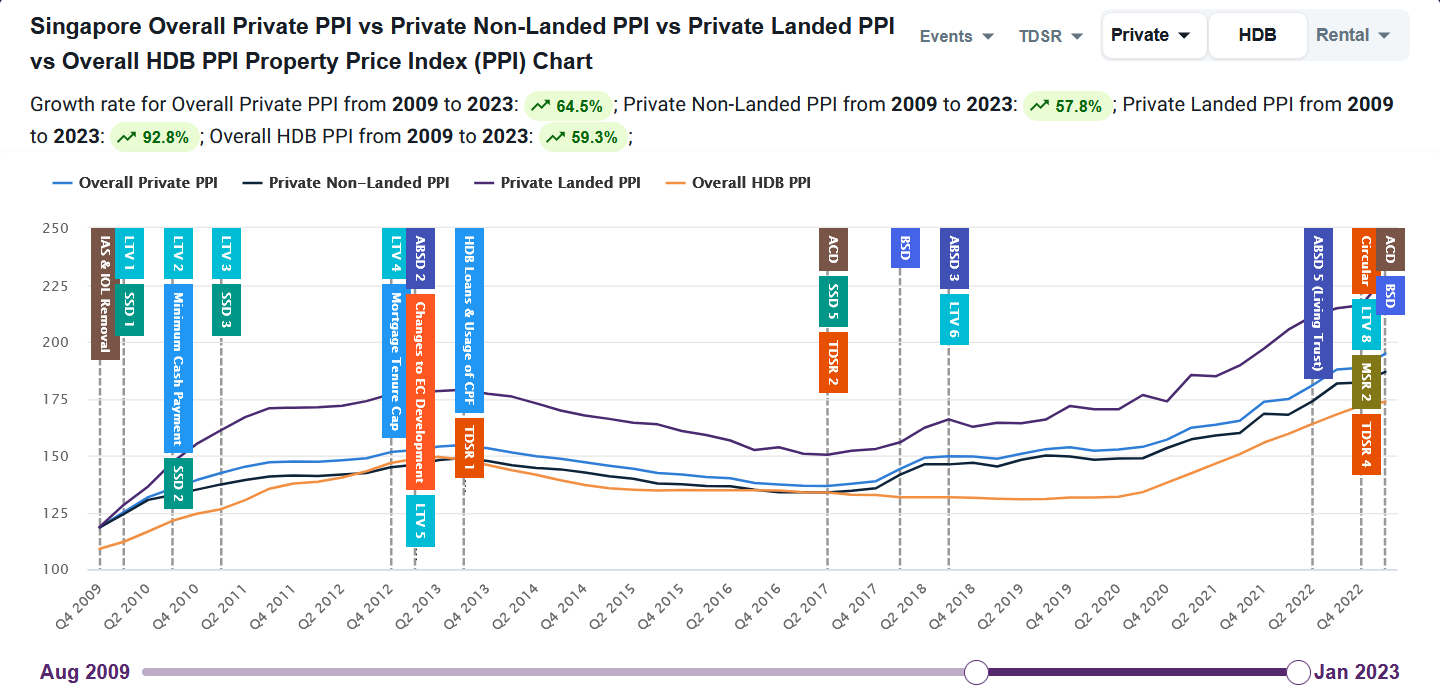

If we take a general look at cooling measures, from the ABSD to loan curbs* and the SSD, we can see they had a stronger collective impact between 2009 to 2018.

There was a special impact on HDB resale prices from 2013 onward when the introduction of the Mortgage Servicing Ratio (MSR) sent resale prices into a tailspin; this lasted right up till the post-Covid-19 period.

In general, though, you can see that the third "cluster" of cooling measures starting sometime in 2013 had a much weaker impact than its predecessors, as prices have risen sharply in spite of them. As for the very latest rounds of cooling measures, their efficacy is yet to be seen.

Nonetheless, we should consider if some of these measures have a bigger impact than others.

*Note that certain loan curbs, such as the Total Debt Servicing Ratio or lower Loan-to-Value limits, were never classified as cooling measures. They are, and always were, fundamental changes to lending policy.

Technically this means loan curbs are not temporary like the ABSD; but this distinction has lost meaning as most industry professionals regard ABSD as "effectively permanent" anyway.

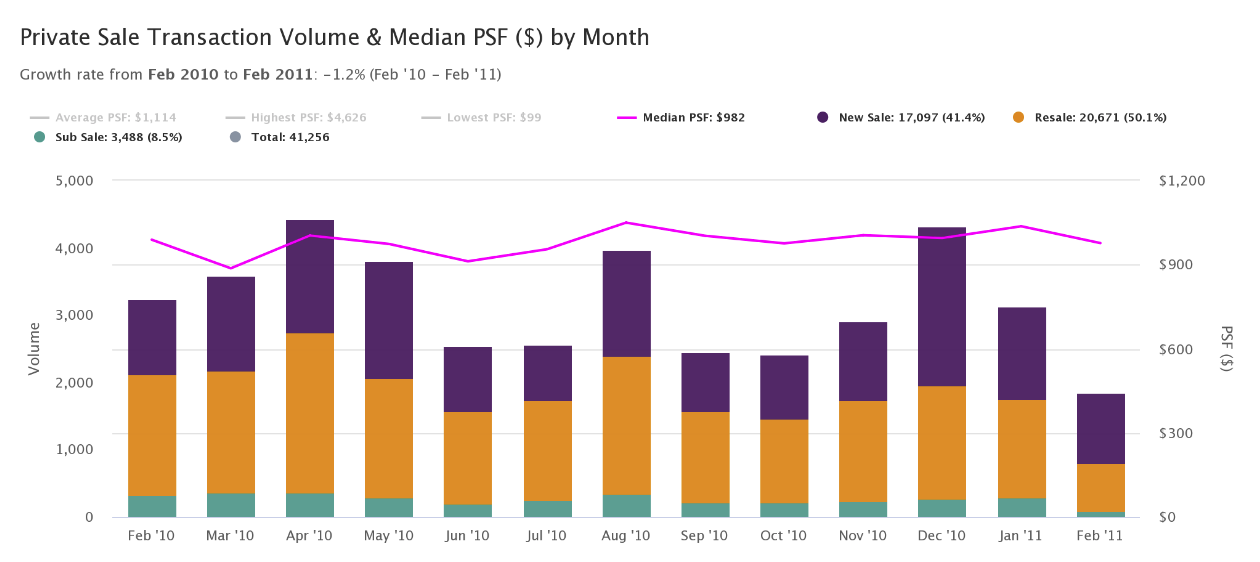

The first time a loan curb was introduced was on Feb 20, 2010. Over a one-year period following the loan curb, prices fell from an average of $989 psf, to $977 psf.

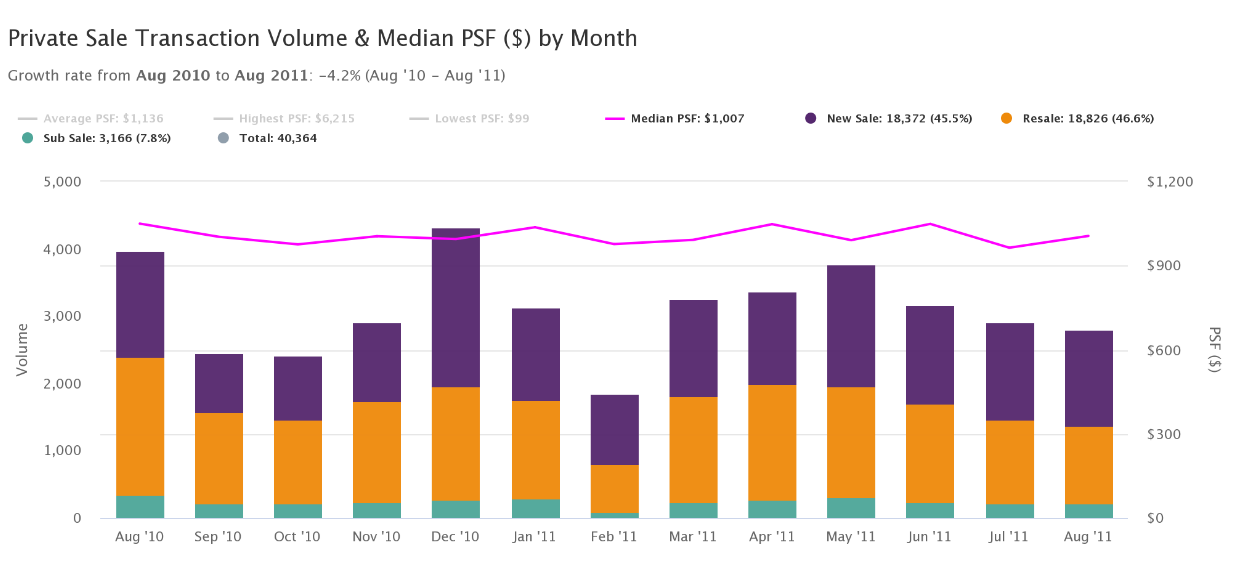

This was followed by a further loan curb in August 2010, where the LTV was dropped to 70 per cent. Also, a minimum cash down of 10 per cent was also required. Again, we saw prices dip:

Over a one-year period from August 2010, average prices dipped from $1,050 psf, to $1,006 psf.

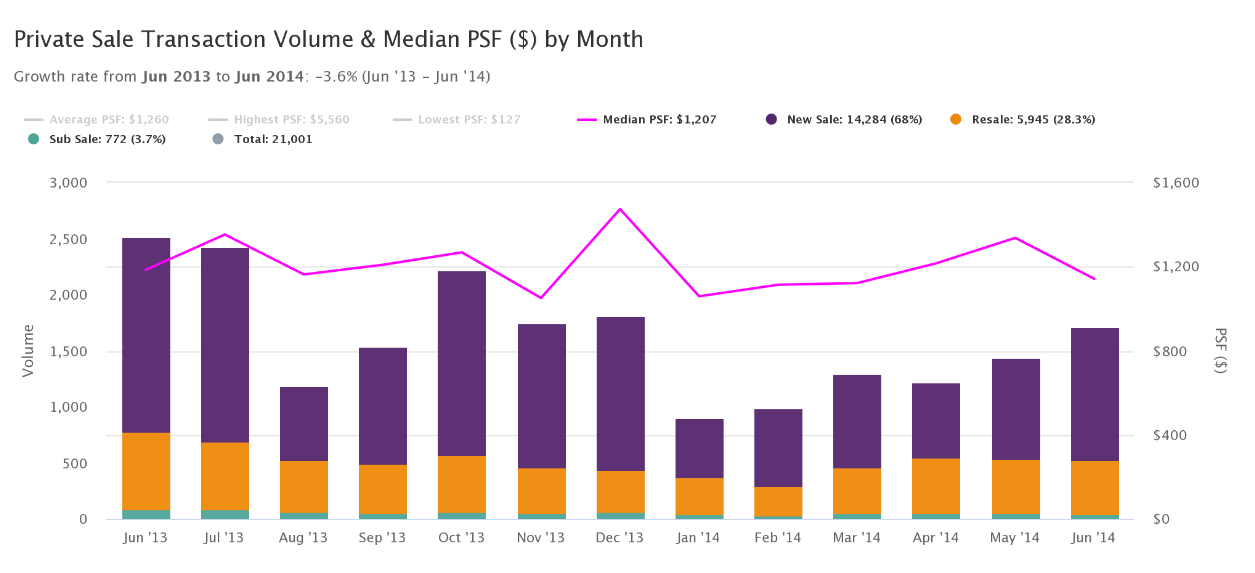

The next biggest loan curb was to land on June 2013. The Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR) capped monthly loan repayments at 60 per cent of the borrowers’ monthly income.

In the year following the TDSR's introduction, average prices fell from $1,353 psf to $1,142 psf.

In July 2021, TDSR was further tightened to 55 per cent. By the following year, we saw average prices fall from $1,502 psf, to $1,408 psf.

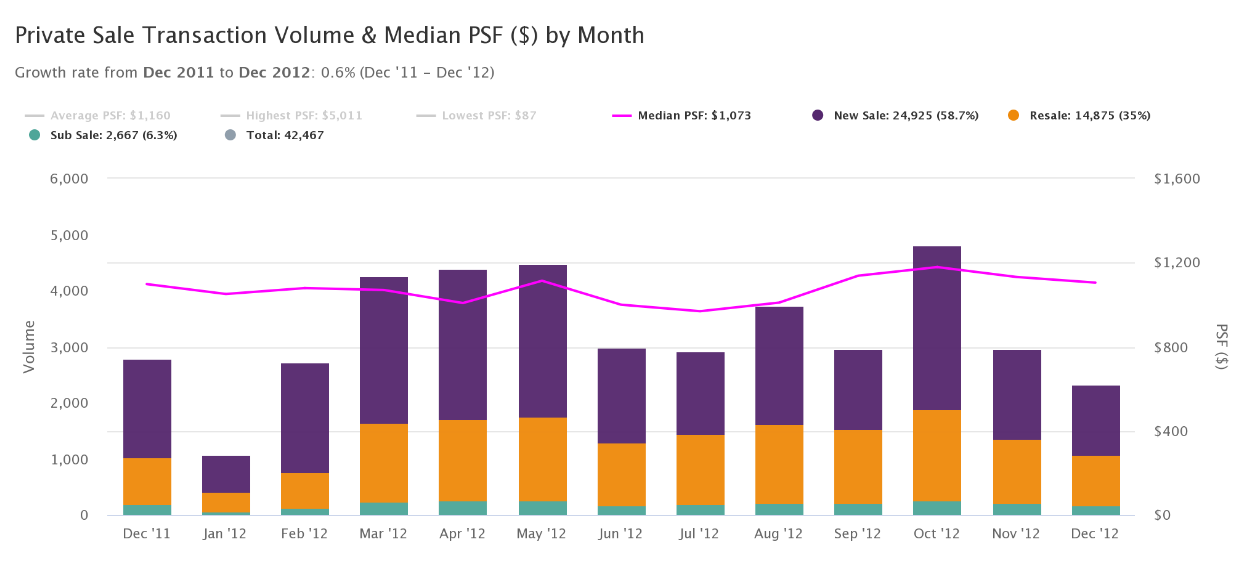

ABSD was first introduced in December 2011. Back then, the ABSD was a mere three per cent for Singapore Citizens buying a third or subsequent property, and just three per cent for PRs buying a second property. It was 10 per cent for foreigners and entities.

Over a one-year period from December 2011, average prices rose from $1,098 psf, to $1,105 psf.

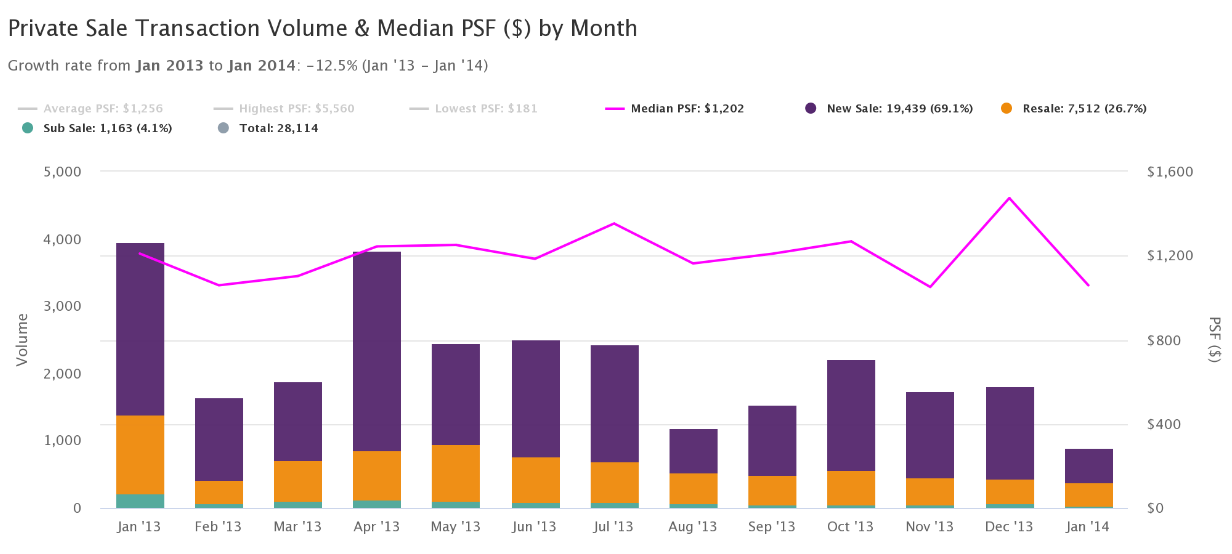

In January 2013, the government hiked ABSD rates again. However, it was also coupled with loan curbs.

This time the ABSD rose to seven per cent for citizens buying the second property, and 10 per cent on the third. For PRs, it rose to five per cent, and 10 per cent on the second or third property. Foreigners and entities paid 15 per cent.

At the same time, the LTV ratios for borrowers were reduced. For those who took a loan tenure exceeding 30 years, or which would last beyond the borrower's retirement age of 65, the LTV would fall to 60 per cent (50 per cent if they had an outstanding home loan).

From January 2013, prices fell from an average of $1,210 psf, to $1,059 psf.

This seemed to set the pattern, as the next two ABD rate hikes (July 2018 and December 2021) saw ABSD rate hikes accompanied by loan curbs; and each time saw price dips.

The next time we saw ABSD rate hikes without a loan curb was in April 2023, and it remains to be seen if this will cause prices to drop. So far from word on the ground, and from most analysts, the predicted impact is only on a small group of investors and foreigners.

Most agents have told us their buyers (the bulk of whom are upgraders) remain undeterred, as they don't pay ABSD anyway.

Loan curbs stop buyers from over-extending themselves; and quite a few people have questioned why HDB does this while the private market doesn't. (HDB caps the MSR at 30 per cent, while TDSR lets you go as high as 55 per cent).

This has allowed "arbitrage" opportunities like buying an Executive Condominium with the MSR ruling (hence why ECs are also priced more affordably), and selling it in the resale market later (which with the TDSR allows for buyers with stronger buying power).

Setting a higher ABSD rate just encourages more spending to cover the tax (or higher CPF usage, if the buyers pay for stamp duties that way). Setting tighter loan curbs has the dual effect of enforcing a higher savings rate, while also helping to cool the property market.

In the long run, loan curbs — when used in moderation — can have the added benefit of ensuring bigger CPF retirement funds.

Almost every seller hopes to cover the ABSD rate via rental income or resale gains. So while the ABSD rate may cool the market in the short run, we're still adding to the price tag: Decades from now, those sellers are going to factor their stamp duties into their asking prices.

This has to be coupled with the fact that Singaporean property owners have a lot of holding power; desperate mortgagee sales are quite rare in this country. This means sellers who have paid, say, 20 per cent ABSD is in no urgent need to sell; and they can easily hold until some offer also covers that 20 per cent they paid.

So stamp duties still ultimately add to home prices, compared to a straight-up loan curb like a tighter TDSR or LTV.

ABSD has, so far, impacted just small demographics. Foreigners, entities, and the small number of Singaporeans who actually own multiple properties are affected.

This is quite different from loan curbs, as even HDB upgraders are restrained by them. This makes it more likely that home prices will moderate, including in districts where investment properties are rarer.

As is, it's mainly foreigner and investor-heavy districts like nine or 10 that bear the brunt of ABSD. This can leave fringe districts to continue seeing strong price growth, which doesn't help the majority of Singaporeans (most Singaporeans purchase private homes in non-central districts, due to the lower quantum).

Also, there is a stark contrast in how loan curbs and ABSD affect an individual's affordability. When we look at a new buyer, an increase in ABSD might shave off somewhere between $10-100k from what they can afford.

This may seem like a considerable amount, but it's often only a fraction of the total cost of a property and can generally be planned for in advance.

On the other hand, adjustments to loan curbs or the Total Debt Servicing Ratio (TDSR) could potentially slash a significantly larger amount from a buyer's affordability. Unlike ABSD, these changes directly impact the loan amount that a buyer is eligible to borrow, which is typically a large percentage of the property's cost.

As a result, even a slight tweak in these limits can drastically reduce the range of properties that a buyer can afford, effectively cooling demand and, consequently, property prices.

In general, we should see ABSD as a tool to control speculation and foreign/corporate investments in residential real estate. That has its place in overall policy-making.

We might, however, consider loan curbs rather than stamp duties as the main tool to lower overall housing prices. In 20 or 30 years from now, the current generation of homeowners will be more thankful that a loan curb forced them into higher CPF savings, than they would be for having paid ABSD.

This article was first published in Stackedhomes.