Singapore housing the most affordable in Asian cities? New report reveals shocking news, but not everyone agrees

In a Reddit post today, it was pointed out that Singapore has the most affordable housing in Asian countries.

That’s a pretty provocative statement, especially in 2022 when home buyers are complaining of sky-high prices on both private and public property. But do the statistics lie, or is Singapore in fact more affordable than we give it credit for? There are a number of key issues in question:

This study was conducted by the Urban Land Institute, which covers 28 cities in five countries, and looked at data in the areas of price comparison, price affordability, rental housing, home ownership, and ease of home purchase.

For the full report, you can view it here.

It’s a long report, but here are a few points that would be interesting to us in Singapore.

The general claim is that HDB costs are, on average, 4.5 times our annual household income. This would make us the most affordable cities for housing, within the Asia-Pacific region.

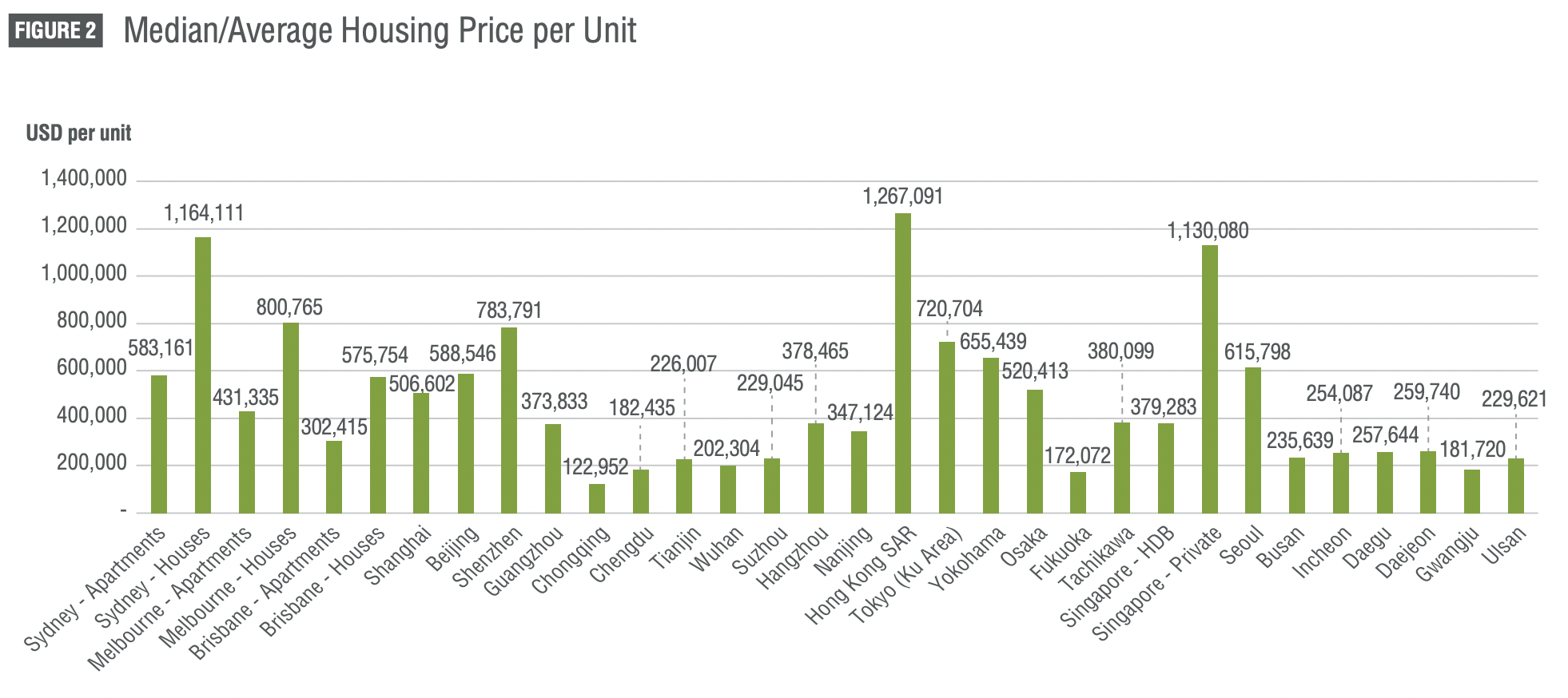

As for private housing, at around 13.3 times annual income; this would still make us rank somewhat in the middle out of all the cities surveyed. Most notably, we are still more affordable as compared to other competing cities like Seoul, Tokyo, Shanghai, Beijing, and Hong Kong.

According to the Ministry of Manpower, median income in Singapore as of 2021 was about $4,680 per month, or about $56,160 per year. Now assuming a dual-income family, the data seems somewhat on-point: it would mean the average HDB flat costs $505,440, while the average private property costs $1,493,856.

For the housing affordability data for HDB, this was based on 2021 resale HDB flat prices, which they established at $379,283 USD, or $529,214 SGD.

Do note that most Singaporeans won’t pay $505,440 for a 4-room BTO flat, for example (it would probably be about $350,000 in the non-mature neighbourhoods, even before grants). This amount is more likely, however, for BTO 5-room flats in some mature towns; and in 2022, it’s definitely possible for a resale 4-room flat.

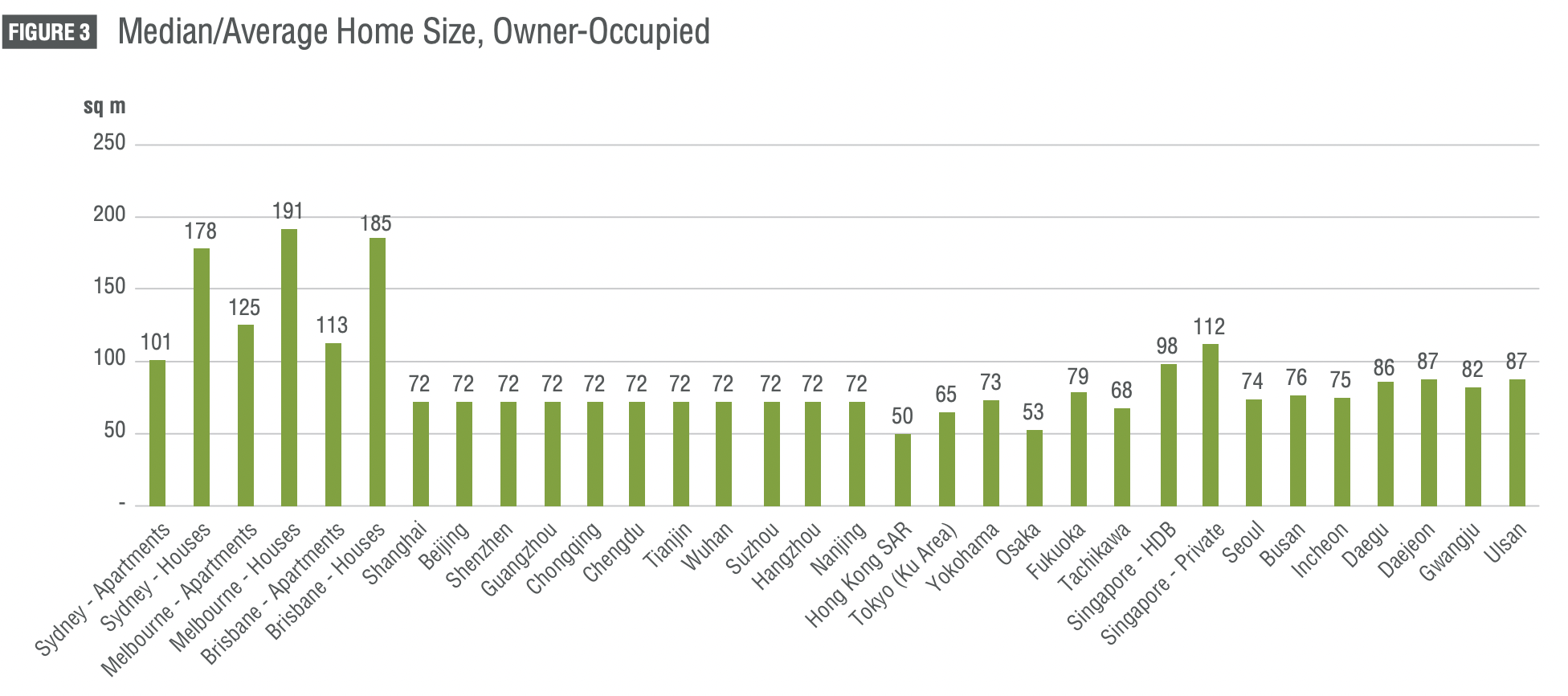

At 98 sqm for Singapore’s HDB, we have some of the biggest home sizes, especially when you compare it to cities in Korea, Japan, China, and Hong Kong (of course). We really only lose out to housing in Australia, with some cities enjoying nearly double the size.

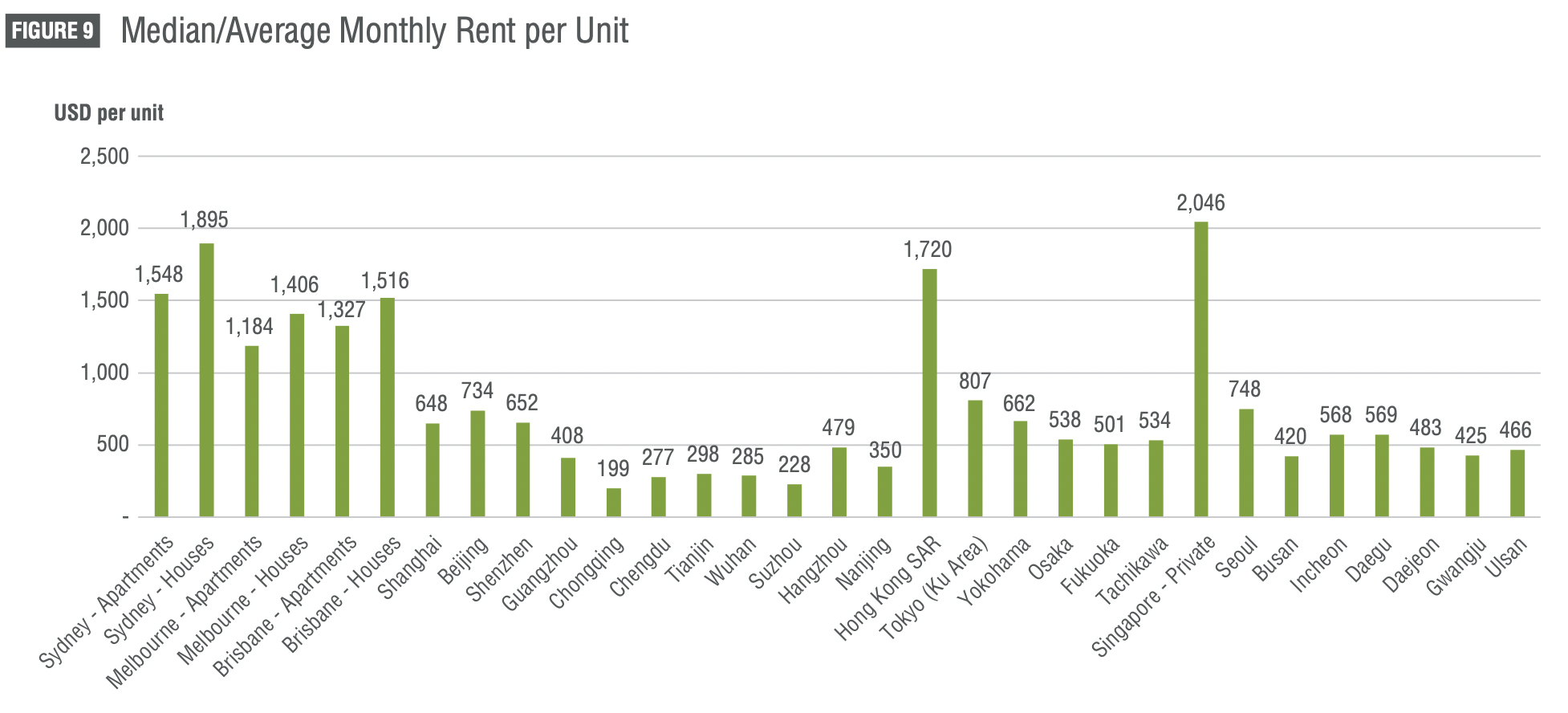

We do have the highest rental rates on the private housing site, even beating places like Hong Kong.

That said, does all of this mean HDB flats are in fact really affordable, even with prices on the rise? Here’s what we need to consider:

In terms of BTO flat pricing, we daresay the majority of Singaporeans can afford at least a 3-room flat; most can probably buy a 4-room. But we should remember that not everyone has access to the BTO market.

For starters, not every Singaporean can wait to succeed at the balloting, and then wait for another four to five years for construction. For those who urgently need a home right now, the pricey resale flat market may be their only recourse. Also, bear in mind that unmarried individuals are restricted to 2-room units for BTO flats (and that gay marriage is not recognised in Singapore).

This is also an issue for Permanent Residents (PRs), as a family with no Singapore Citizens cannot buy a BTO flat at all. If both spouses are PRs, they both need to wait the mandatory three years before they can own a resale flat.

So there is a subset of Singaporeans who are restricted to the resale flat market. We have no way of knowing how big this demographic is, but we do know that flats are likely to be less affordable for them.

They’re forced to contend with rising Cash Over Valuation (COV), and the simple fact that resale flats are so much pricier.

The BTO system itself may have something to do with this

If there were more new flats available, and a shorter waiting time, fewer Singaporeans would be stuck within the pricey resale market. However, HDB uses the BTO system to avoid over-building flats, after a massive oversupply incident in the 1990s.

It’s been more than 30 years now though, and HDB should be better able to predict the number of units needed. It may be time to relook the slower BTO system, and simply build in the expectation of future needs (at least, for the predictable in-demand estates).

When it comes to an essential need like housing, it may be better to have a few more units than we need, rather than the other way around.

Few people seem to question the dual-income scenario that we now take for granted. It’s generally assumed that more than one member of the family will contribute to the mortgage. But have we considered what this means in the broader sense?

When dual income is the norm, what happens if one contributing member can no longer work (e.g., a spouse is rendered medically unable to work after an accident)? In a single-income household, there may be a last-ditch safety net, in which the other spouse can then go out and work. That’s not necessarily a big help, but it’s still better than a dual-income couple where both must be working to cover costs.

There are no statistics on how many Singaporean households are now dual income, nor how much this number has increased over the decades. Anecdotally, we’re often told that single-income families were more viable in our parents’ era; and we think most Singaporeans past the age of 40, if they think back, will recall that’s probably true.

The point here is that, while we’re busy looking at median-income-to-home-price numbers, we may not be paying attention to where the rising income is from. It may not be that Singaporeans are getting richer and able to buy pricier homes: it may simply be that we’ve normalised dual-income lifestyles.

Apart from being a little less safe, as mentioned above, dual-income lifestyles can mean less family time or a more highly stressed lifestyle. If we now require such a trade-off, does that mean our housing is truly affordable?

On the issue of a 99-year lease, this is a topic that tends to veer into semantics. Say, for example, we accept that HDB flats are leased and not owned.

A $505,440 flat for 99-years comes to a rental rate of just over $425 a month, for 99 years. It’s still far from unaffordable.

The other restrictions though, are a different issue. We’ve already pointed out that some Singaporeans can’t buy BTO flats, and are confined to pricier resale flats (see point 1). But besides this, we have issues such as who we can sell out flat to, and when.

Foreigners can’t buy HDB flats, and the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP) can lower the pool of prospective buyers. Likewise, we need to wait out the five-year Minimum Occupancy Period (MOP) before we can sell, or 10 years for Prime Location Housing (PLH) flats.

These do represent significant drawbacks, compared to private housing. However, do they represent an issue of affordability?

If, in your perspective, “affordable housing” means being able to upgrade at some point, then this may be a major point of contention. But if your definition of “affordable housing” is just somewhere comfortable to stay – and you don’t care too much about issues like resale gains – then none of these restrictions is a significant drawback.

It’s not true that, because Singapore is so small, there will never be cheaper areas. It’s a simple fact that flats in, say, Yishun are cheaper than flats in Bishan. You can always opt for a less mature neighbourhood. But this doesn’t discount the entire point.

To be precise: What you can’t do is escape to an area, where prices are low enough to fulfill certain lifestyle needs. For example, say it’s important to you to have a koi pond, or a backyard for your gardening.

You can find some places where landed properties are cheaper. But there’s no way to travel so far out from the central area, that you can find a decent landed property with a garden and two-car garage for the price of a 4-room flat.

This is different from some places like Australia, where you could choose to live all the way out in the sticks. So long as you move far enough, you would eventually find a landed space that matches your budget.

Singapore just doesn’t afford you the same range of options; even if you are willing to endure extreme isolation for your dream home.

While measuring income to home price is one way to determine affordability, it overlooks an important point: Singaporeans have one of the highest savings rates in the world.

Consider our CPF accounts, which we use for housing: assuming the usual contribution of 37 per cent, the average Singaporean ($4,680 per month) is setting aside around $1,731 per month. At 2.5 per cent guaranteed interest, this comes to north of $230k after just 10 years of work.

Now if we take a Singaporean who earns less than the average – say $2,500 per month – the contribution would come to about $925 per month. Over 10 years, this still comes to over $120k.

Keep in mind this is for just one person, and it’s usually couples who buy HDB flats, so the CPF savings of both can be tapped.

Due to these high savings rates, it may be a bit misleading to gauge affordability on our income level alone. Many Singaporeans can afford pricier homes than their income level would suggest, thanks to a larger CPF nest egg.

If you’ve often wondered how so many people are buying $800,000+ resale flats, this may be where the answer lies.

We haven’t considered a whole slew of other factors – such as how many dependents the homeowner has, mobility issues that require them to live closer to work (this can drive up the price), or what they’re personally comfortable with spending each month.

We know that some homeowners consider 30 per cent of household income (the current HDB Mortgage Servicing Ratio) to be an unacceptable level of expenditure, due to their unique financial situation.

All of this makes it impossible to draw a conclusion across the board, as to whether HDB flats are affordable. We can, however, surmise the following:

Overall though, we have to conclude that most Singaporeans are able to afford at least a BTO flat; and it’s a bit difficult to measure affordability against other countries.

Comparing a BTO flat to a private apartment in Tokyo is a real apples-to-oranges attempt, and we don’t think there’s a conclusive way to say Singaporeans are better or worse off than Japanese/Australian/Chinese, etc. counterparts.

Despite all everyone may say, or that we may point out as issues of the property market, we should really also be aware of how fortunate we are as a whole.

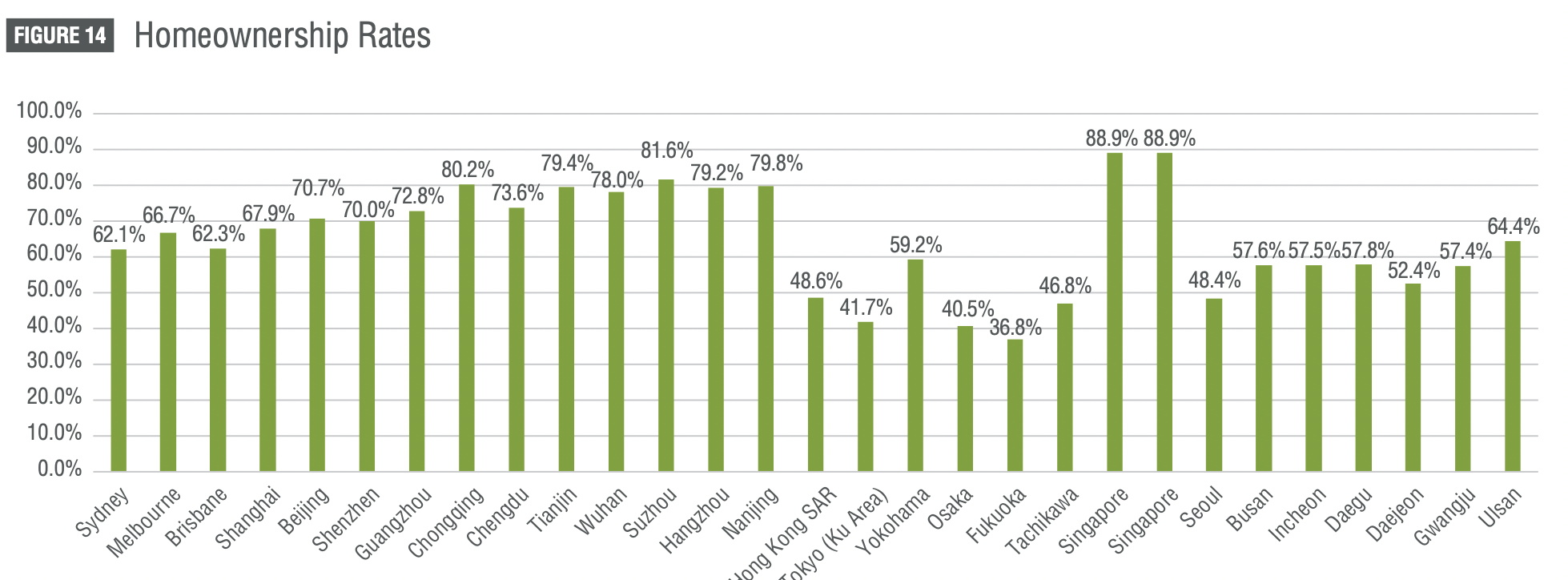

Rising property prices are a problem that every major country is grappling with, and to still have such a high homeownership rate despite everything else is something to be commendable. Especially so when you look at the homeownership rates from the other cities, and it gets even more apparent that we come out on top.

This article was first published in Stackedhomes.