PE2023: They know I have not been a fly-by-night, says Tharman

Singapore erupted in excited chatter when Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam announced on June 8 that he was resigning from his post as Senior Minister to run for president.

Understandably so, because both opinion polls and election results over the years have indicated that he was the most popular People’s Action Party (PAP) politician. In the last general election in 2020, he led Jurong GRC to a solid 74.62 per cent victory – the highest for the party.

Some said Mr Tharman would be a “nuclear option” who would obliterate other presidential candidates. Others lamented that it would be a gross misuse of the talents of a creative and effective reformer, one who has left a positive imprint in finance, welfare, education and other areas.

The 66-year-old brushes off the da cai xiao yong – the Mandarin equivalent of using a sledgehammer to crack a nut – analogy.

“I’ve never thought too highly of myself, honestly. A lot of my life has been a matter of luck and circumstance. Obviously, I take whatever I do very seriously and apply myself, and I have some capabilities.

“But you contribute because you want to see things change for the better for others, rather than contribute because you’re hankering for a certain position in life. And I’ve never had that ambition throughout,” says Mr Tharman whose father is the late Professor Kanagaratnam Shanmugaratnam, Singapore’s “father of pathology” who set up the Singapore Cancer Registry.

“I never planned my career,” says Mr Tharman, an economist who cut his professional teeth at the Monetary Authority Of Singapore (MAS) and, among other appointments, also served as Senior Deputy Secretary for Policy at the Ministry of Education before entering politics in 2001. He was Education Minister for five years, Finance Minister for nine years, and served as Deputy Prime Minister from 2011 before becoming Senior Minister in 2019.

“I never had an ambition to be the managing director of the MAS or anything else. I never planned to be a minister, let alone a deputy prime minister or senior minister, and I never planned to be a president,” he says.

“But at each stage of life, you have to make the judgment: What is the right next step? It’s not an ambition you set early in life, and then you work your way towards it. You just make a decision of what’s the next right step for how you can serve Singapore.”

The time, he believes, is right to step up to help the country navigate a rapidly changing world as president.

“The next president has to be a president for the new future for Singapore. It’s going to be a different future, a more challenging future.”

Times are changing, he says.

“In the next five to 10 years, a new prime minister is going to have to govern Singapore with a team, and it would be a Singapore with more challenging domestic circumstances, challenging in the sense that we’ve got to manage a more diverse population. The new prime minister and his team will also have to make sure that Singapore is held in high respect internationally,” he says.

Given the troubling and troubled phase in global affairs, Mr Tharman says that would not be easy.

“It’s not just the US against China, although that’s the most serious part of it. It’s basically a gradual fragmentation of the world system. And small countries have to find a way of not just surviving, but being respected.”

It worries him.

“I’m deeply concerned about Singapore’s future. I think we’re in for very different times, we’re going to go through a transition, but no one knows exactly what comes at the end of the transition, especially globally.”

Domestically, he is more sanguine.

“We’ll be able to manage a good landing here in a very different society and possibly a different political mood. The centre of Singapore politics is strong enough, and I don’t just mean the PAP, I mean, just the broad centre in Singapore politics is strong enough to evolve and keep us a democracy that people have trust in.”

This is despite the spate of controversies – the corruption probe against Transport Minister S. Iswaran and the inappropriate relationship between former Speaker of Parliament Tan Chuan-Jin and former Tampines GRC MP Cheng Li Hui – which have dogged the PAP.

“I don’t think there’s a deep rot in the system, either within Government or in politics, in general. There’s been a dent to confidence, and it can be repaired and trust can be rebuilt. And that applies both to the Government, to the PAP, as well as to the Workers’ Party. I think we can both rebuild trust, and have to. But I don’t see this as a deep rot in the Singapore system.”

Weathering the vicissitudes of geopolitics and an increasingly fractured world as a small country worries him more. That is why he is standing for president; he believes his own standing from various international leadership roles will be an asset.

Reportedly shortlisted in 2019 to be the next head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Mr Tharman was the first Asian to head the International Monetary and Financial Committee, the policy advisory committee of the IMF in 2011. Among other heavyweight appointments, he also chaired the Group of Thirty, an independent global council of economic and financial leaders from the public and private sectors, and currently co-chairs the Global Commission on the Economics of Water, which aims to redefine the way the world governs water for the common good.

“I’ll be able to play a significant role in ensuring Singapore’s standing internationally in each of the major countries, but also in global organisations... (I will make sure) the way we contribute to the global good not only remains intact, but is enhanced,” he says.

Mr Tharman is sitting in a shipping container which has been converted into an office at the Tasek Jurong Youth Hub in Taman Jurong, where he and his wife Jane Yumiko Ittogi have spent the last 22 years trying to better the lives of its denizens, especially disadvantaged children and youth. He smiles when asked how else luck and circumstance have changed his life.

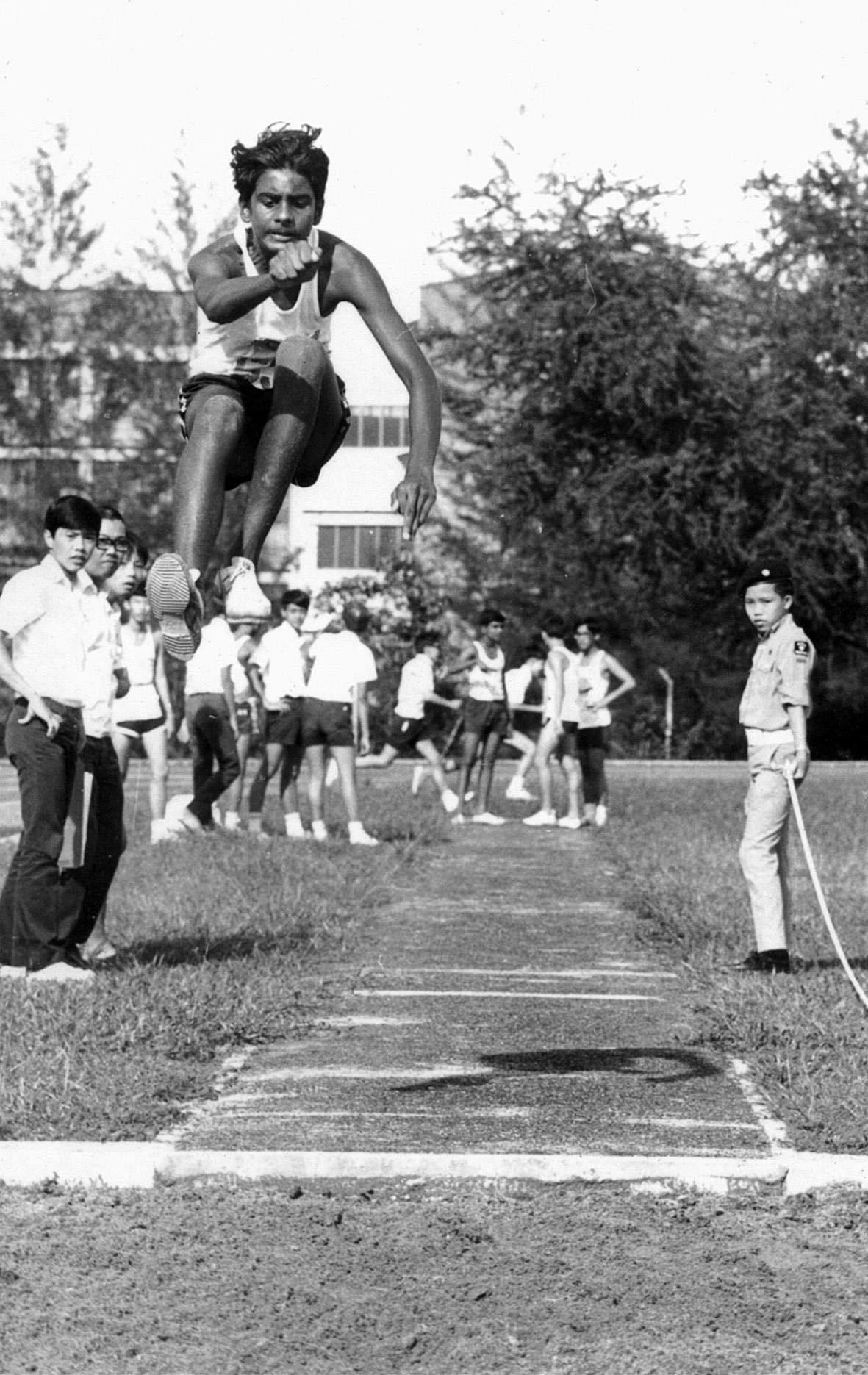

“First, if I’d not been hit by a very serious illness in my late teens, I would have stayed with sports for a long time and become a very serious sportsman,” says the Anglo-Chinese School alumnus who was diagnosed with a severe case of anaemia at 17. The condition affected his heart, and required him to pop more than 20 pills a day for four years.

Studies took a back seat then.

“Every competition that happened within the school, I was there. As long as there was a ball, I was involved,” says the athlete who played hockey, football, rugby, volleyball and sepak takraw, either competitively or at the school level.

“It may have then led to a different life. I don’t know what I would have done after that. I would have done something, I’m sure.”

Meeting his wife – a former lawyer now focused on arts education and community work – in London was also engineered by serendipity. Now in her late 60s, she had just completed her master’s in law while he was about to start his undergraduate studies at the London School of Economics (LSE).

“She had completed her studies by the time I got there, but we had the same group of friends, the same circle of friends (who were) studying social issues.”

It was a meeting of mind and soul.

“We’ve always been close intellectually, emotionally, and in our motivations for what we are doing, in very different ways. She has been working on the ground throughout. I entered politics, working on the ground very closely with her and others, but also working in Government. But our thinking has been very similar, and we’ve always discussed issues together... with regard to the type of society we hope to play our small part in advancing,” says the father of four.

A student activist in his youth, Mr Tharman says his social conscience developed in his late teens and early 20s.

It probably explains why he loves Space Oddity, one of the biggest hits of singer-songwriter David Bowie.

“Ground Control to Major Tom

Your circuit’s dead, there’s something wrong

Can you hear me, Major Tom?”

The song – which is among the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame’s 500 Songs that Shaped Rock ‘n’ Roll – and its lyrics have spawned countless interpretations. Some say it’s Bowie’s confrontation with his drug-addled past, others say it’s his meditation on isolation and the human condition. Music writer James Perone, meanwhile, believes Major Tom is a metaphor for individuals who are clueless, but make no effort to learn, about the world.

Mr Tharman was not and is not a Major Tom.

“I was already very concerned not just about social inequities in my late teens, but the way ordinary people were viewed,” he says, adding that he spent a lot of time walking or taking public buses all over Singapore to see how people lived.

During his national service and university years, he read voraciously and became a serious student of social policy and possible alternatives to a capitalistic market economy.

By the time he completed his degree at LSE, Mr Tharman – who went on obtain a master’s in economics from Cambridge University and a master’s in public administration from Harvard University – came to the conclusion that “there were no radical economic alternatives to the current system of a market economy tempered by a state that provides support for the poor and, to some extent, for the middle class”.

“There was no radical alternative to that basic social democratic construct. But the moral case for doing more to help ordinary people, and particularly poorer people, remains strong, and we have to find good solutions for that, and it was important for me all the way through. I’ve never changed in that regard.”

His beliefs about how he can help to provide better lives evolved with a deeper understanding of the realities of economies – both domestic and global.

“In Singapore, I was working at the MAS as a chief economist, and then later, financial regulator and managing director. You know that your first priority is to make sure that the Singapore economy is able to compete with the world, people are able to have jobs, and their incomes are able to rise over time. That’s your first priority, and you can’t achieve social justice without that.”

It prompted him to make the “adult” decision to enter politics in 2001.

“Having spent about 20 years being of service to the public in the civil service, I wanted then to spend the rest of my time being able to serve people on the ground, to help create initiatives on the ground.”

He was also keen to rethink educational, social and economic policies.

“I knew I could only do that if I joined the Government and became an MP on the ground. (But) it was the same me informed by the same practical idealism,” he says, adding that his former Cabinet colleagues, and even the opposition, know he has his own convictions.

In 2001, he expressed his scepticism about the 1987 arrest and detention without trial of 22 people accused by the government of being Marxists conspiring to overthrow the state.

“...although I had no access to state intelligence, from what I knew of them, most were social activists but were not out to subvert the system.”

Asked what he would do should the same scenario crop up if he were elected president, he says: “I would study the facts and I would take a position that is informed by what I believe is right. I would not be the first to do so.”

“As you know, in the previous Cabinet at the time, there was at least one minister who took that view,” he says, referring to former foreign minister S. Dhanabalan who also felt uncomfortable over the Marxist arrests and left the Cabinet in 1992 after 16 years in politics.

To detractors who say his time in the Government will make him less than independent if he were elected president, Mr Tharman says: “I’ve never had to compromise my values and my basic motive for being in politics, which is to build a fairer and more socially just society.”

He attributes it to the strengths of the system.

“We debated every issue, and I think we have shifted the ground of our policies very significantly in the last 15 to 20 years. And that was a process of debate, the consensus building, that was extremely important and which I was a very active member of. So when I say I am independent-minded, this is not something that I’m suddenly springing up with because of the presidential election. It goes back to my youth, it goes back to my career in the civil service, including the ups and downs I had, and how I stood my ground all the way through.”

He adds: “And it goes back to the last 20 years, the second half of my service in Government itself. That’s the way we operated, and that’s the way I operated.”

The presidency, he emphasises, must never be about taking an independent stance or disagreeing with the Government just for the sake of it.

“You need that combination of an independent mandate, independence of mind, a person with convictions of his own, but you also need trust in the system for the system to work well. Otherwise, without that trust, not only will the system get jammed up domestically where you’re unable to make bold decisions in crises that are needed for Singapore, but you’re also unable as a president to represent the country abroad very well because if you are at constant loggerheads with the Government, then you can’t represent the country well. Other countries won’t take you seriously.”

He hopes Singaporeans, especially the young and those new to the presidential election, will leave politics out of the equation when casting their vote.

“Remember, this is an institution that is above politics. We have to look at people based on their personal character, their convictions as revealed by their track record. We have to choose who best can represent Singapore internationally, and who best can symbolise that solidarity that we’re going to need more of in the years to come, and who best has the knowledge and capabilities to exercise the executive powers,” he says.

Executive powers aside, one of the things he hopes to do if elected president is to help deepen Singapore’s multicultural identity, and develop a “third space”.

“It’s not just the first space of us keeping alive our own cultures. It’s not the common space where we all compromise and keep race and religion out of everything – in education and in a large part of public life. It’s a third space, where we actually participate in each other’s cultures,” says Mr Tharman whose campaign motto is “Respect For All”.

The hardest part about his presidential bid, he says, is saying goodbye to the residents in Jurong he has served for the last 22 years. He has a ready answer for critics who say he is letting down the people who voted for him.

Several big global organisations, he lets on, have courted him to take on leadership roles in the last decade. He has rejected most of them.

“I just told them straight: ‘I’m sorry... I was elected by the people in my constituency, and I’m not leaving. And I don’t want to leave my country either because serving my country is the biggest privilege in my life’.”

But putting himself forward for president is different.

“It would have been perfect if it came after the end of an electoral term. But certainly, from my interactions with people on the ground in Taman Jurong after I made my announcement, there was sadness and there was respect for what I had decided to do. I can say that quite comfortably. People were sad that I was leaving. My wife and I were also very sad to leave.

“But they understood this decision, and many of them came up to me to say, ‘I really support your decision’.”

He says: “I think Singaporeans have a sense of what’s important. I’ve been here not just for 22 years, I have been here several times a week for 22 years. They know I haven’t been a fly-by-night.”

This article was first published in The Straits Times. Permission required for reproduction.