How much plastic does a person ingest weekly? A credit card’s worth in weight on average

SINGAPORE - Fancy a pinch of plastic with that shellfish dish?

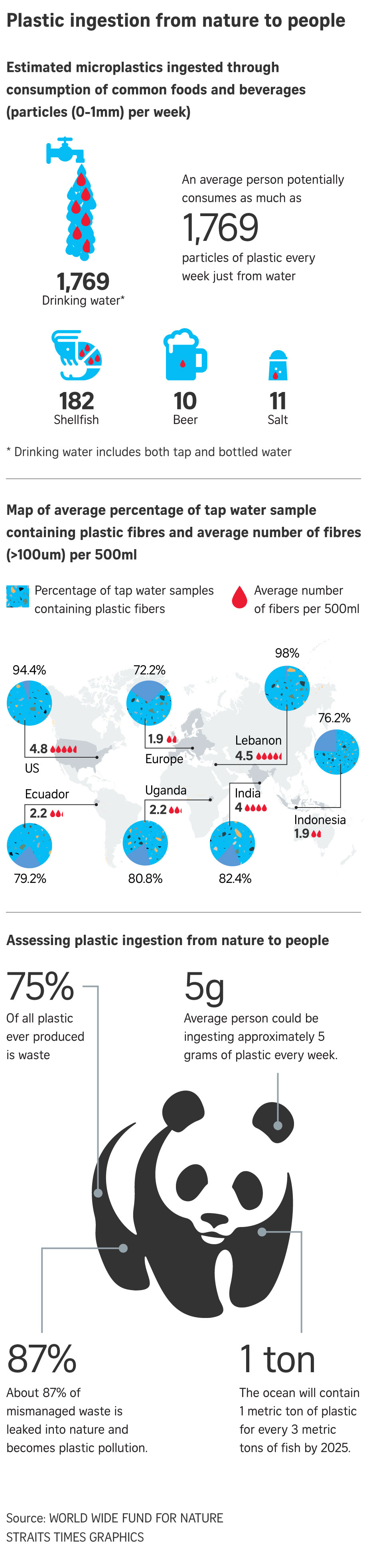

New research combining the results of more than 50 studies globally has found that on average, people could be ingesting about 5g of plastic every week - equivalent to a credit card - in the air they breathe, the food they eat and especially, the water they drink.

This amounts to about 100,000 tiny pieces of plastic - or 250g - every year, said the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the University of Newcastle on Wednesday (June 12). The study was commissioned by WWF and done by the Australian university.

"These findings must serve as a wake-up call to governments. If we don't want plastic in our bodies, we need to stop the millions of tons of plastic that continue leaking into nature every year," said WWF International director general Marco Lambertini.

To tackle the plastic crisis, he said, urgent action at the government, business and consumer levels was needed, as well as a global treaty with global targets to address plastic pollution.

The research was the first to combine insights from the studies across the world on the ingestion of plastic by people, said the WWF.

Out of a total of 52 studies it included in its calculations, 33 looked at plastic consumption through food and beverage. These studies highlighted a list of common food and beverages containing microplastics, such as drinking water, beer, shellfish and salt.

The WWF, however, noted the findings may be an underestimate because the microplastic contamination of staple foods such as milk, rice, wheat, corn, bread, pasta and oils has yet to be studied.

Microplastics are plastic particles under 5mm in size, though they can be much smaller.

The largest source of plastic ingestion was drinking water, with plastic found in water including groundwater, surface water, tap water and bottled water all over the world.

Another key source was shellfish, accounting for as much as 0.5g a week. Shellfish are eaten whole, including their digestive system, after a life in plastic-polluted seas.

But inhalation represented a negligible proportion of microplastics entering the human body, though this might vary heavily depending on the environment. Results from 16 papers focusing on outdoor and indoor air quality showed that indoor air is more heavily plastic polluted than the outdoors, owing to limited air circulation indoors and the fact that synthetic textiles and household dust are among the most important sources of airborne microplastics.

While the university's effort represents a synthesis of the best available data, it builds on a limited set of evidence, and comes with limitations, the WWF acknowledged in the report: No plastic in nature: assessing plastic ingestion from nature to people, which was was prepared by strategy consulting firm Dalberg Advisors.

It also said further studies are needed to get a precise estimate.

The WWF said scientists are working to obtain more precise information on pollution from plastic, how it is distributed and how much is consumed.

Some important areas the research community is exploring include mapping the size and weight distribution of plastic waste particles and how plastic particles − when consumed by an animal - travel into muscle tissue.

For instance, scientists are tracking plastic in the oceans to create a 3D map of ocean plastic litter, it added.

Another key research area is identifying the health effects of plastic ingestion on humans, as these are not well documented yet.

There are also economic consequences to all that plastic: the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates the economic impact of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems to be at least US$8 billion a year.

The current global approach to addressing the plastic crisis is failing, said the WWF.

It called for governments to take greater action by, among other things, supporting further research, establishing a global scientific body to assess and synthesise the best available research on plastic and microplastics in nature, and agreeing to a legally binding international treaty to stop plastic pollution from leaking into the oceans.

Find out how much plastics you are consuming at yourplasticdiet.org

In Singapore: drinking water is free of microplastic

Monitoring by national water agency PUB shows Singapore's drinking water is free from microplastics, said Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli in Parliament in 2018.

Singapore is monitoring international developments on microplastics, including microbeads in cosmetics, and is committed to keeping the country's watercourses free from pollution, he said in a written reply.

Microplastics, which include microbeads, are removed at waterworks that treat water for potable supply. At Singapore's NEWater and desalination plants, microplastics are removed using reverse osmosis membranes. PUB also ensures that all used water is collected and treated at water reclamation plants to internationally-recognised discharge standards, he said.

During the treatment process, microplastics in used water are substantially removed as sludge and incinerated. The bulk of the treated used water is further processed and reclaimed as NEWater. As a result of these processes, only a minuscule amount of microplastics is discharged into the sea, he noted.

PUB is also looking into incorporating membrane bioreactor technology in Singapore's used water treatment process to further improve the microplastics removal rate.

The Singapore Food Agency (SFA) told The Straits Times that while microplastics is an emerging area of concern, the World Health Organisation(WHO) has indicated there is no evidence currently that it has an impact on human health.

Still, it is investigating the potential health risk of microplastics in drinking water, and other agencies, such as the European Food Safety Authority and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, said more scientific evidence would be needed for such an assessment, said the SFA.

At present, no country has imposed legislation to regulate microplastics in food products, SFA noted, adding that it routinely takes samples of locally available food, including seafood and bottled water, for testing to ensure compliance with food safety standards, which are aligned with international standards.

"We will continue to monitor international scientific developments on the issue of microplastics and implement appropriate measures to safeguard the health of our consumers when necessary," said an SFA spokesman.

RECORD RISE IN PLASTIC PRODUCTION AROUND THE WORLD

Since 2000, the world has produced as much plastic as all the preceding years combined, a third of which is leaked into nature. The production of virgin plastic has increased 200-fold since 1950 and has grown at 4 per cent a year since 2000. If all predicted plastic production capacity is reached, current production could increase by 40 per cent by 2030.

- One-third of plastic waste ends up in nature, accounting for 100 million tonnes of plastic waste in 2016. More than 75 per cent of all plastic produced is waste. If nothing changes, the ocean will contain 1 tonne of plastic for every 3 tonnes of fish by 2025.

- Microplastics are defined as plastic particles under 5mm in size. Primary microplastics are plastics directly released into the environment in the form of small particulates which can be found in microbeads in shower gels, for example, while secondary microplastics originate from the degradation of larger plastic like plastic bags.

- Plastic has been found at the bottom of the Mariana trench and in Arctic sea ice, in addition to covering coastal ecosystems and accumulating in ocean currents in all parts of the world.

Animals get entangled in large plastic debris, leading to injury or death. Wildlife entanglement has been recorded in more than 270 different species, including mammals, reptiles, birds and fish.

Animals also ingest large quantities of plastic that they cannot pass through their digestive systems, resulting in internal abrasions, digestive blockages, and death. Toxins from ingested plastic also harm breeding and impair immune systems.

This article was first published in The Straits Times. Permission required for reproduction.