'Revenge porn' victims speak out: 'Will he take pictures of me when I'm not looking?'

SINGAPORE — “Oh wow, she’s hot,” read a stranger’s text on the phone of Nora’s boyfriend.

She saw his response: “Yeah, do you want? I can share with you.”

When Nora (not her real name) discovered in 2024 that her partner had been trading intimate photos of her with another man, she was blindsided.

“I never suspected it,” says the university graduate in her 20s. “It kind of knocked the wind out of me, and I just went into shock.”

She deleted all the photos she could find on his phone, but this betrayal marked the end of their fraught year-long relationship.

To this day, the discovery still haunts her. “That was what I found, but I don’t know if he had sent more things or if he had shared it with other people. I don’t know the full extent of it,” she tells The Straits Times on condition of anonymity.

Nora sought counselling, but kept it a secret from her family. She considered reporting the incident to the authorities, but ultimately held back.

“Because they obviously need to ask all the questions, they need all the details. I didn’t want to deal with that,” she says, referring to the hurt of having to recount and relive the experience over and over again.

“And for what kind of payoff? There was no certainty that anything could really be done. And I didn’t want to provoke him,” she adds. “I really wanted to just move on and not have anything to do with this person any more.”

Nora is among a growing number of Singaporeans who have experienced image-based sexual abuse (IBSA), which refers to creating, sharing or threatening to share sexually explicit images or videos of someone without his or her knowledge or consent.

The more colloquial term for this is “revenge porn”, but there has been a pushback against that label.

“Labelling such abuse as ‘revenge’ implies that the survivor initiated the harm and deserves this retribution,” says Sugidha Nithiananthan, director of advocacy and research at gender advocacy group Aware. “Perpetrators of IBSA are not always motivated by revenge.”

A 2025 study by researchers from Google and RMIT University in Australia of over 16,000 adults in 10 countries — including Australia, South Korea and the United States — found that more than one in five had experienced IBSA.

Local non-profit SG Her Empowerment (SHE), which runs the SheCares@SWCO centre supporting targets of online harm, says it was contacted by 46 people in 2024 for assistance regarding IBSA. This compares with 27 clients in 2023, when the centre was launched.

Aware’s Sexual Assault Care Centre received 73 calls involving such abuse in 2023 — with the majority of the cases involving non-consensual creation or obtainment of such images.

They estimate the incidence of IBSA is likely much higher due to stigma and shame preventing many from seeking help.

All the five women and one man who shared their experiences with ST requested anonymity. Only one of them sought help from Aware and three made a police report.

Survivors of IBSA say navigating this form of abuse is doubly difficult, not only because of the intimate nature of the betrayal by someone they once trusted, but also because of pervasive victim-blaming.

Worse, they fear a lingering impact as these images — once created or shared — gain a digital permanence that may follow them for life.

Whenever Sarah (not her real name), a 25-year-old university student, and her former boyfriend, a fellow student, engaged in sexual activities, he would ask if he could take pictures to “remember the moment”.

She says: “I disagreed because I understood the danger of having these kinds of pictures taken, especially with all the leaks and stuff.”

Towards the end of their eight-month relationship, Sarah discovered her partner had secretly taken intimate images of her without her consent. When the relationship soured, he “weaponised” these pictures against her. She was 22 at the time.

“Because our relationship didn’t end on very good terms, he tried to threaten me with these pictures. I was going through a lot mentally, so I didn’t know how to handle it,” she recalls.

After consulting her sister, Sarah reported the matter to the police, out of fear her ex might share the pictures.

“Everything from there to the day they told me that all the pictures were deleted, it was just a waiting game. Could it be leaked? What is he going to do? What are the police doing?” she says.

Her ex continued sending her threatening messages when he wanted to reconcile and she did not. Her “heart dropped” whenever she received them, sometimes in the middle of class. With the case hanging over her head, she struggled with suicidal ideation and began to withdraw from her friends.

Two months later, the police informed her that her ex had agreed to delete the material. They also notified her that he had received a written advisory to refrain from conduct that may amount to a criminal offence, and no further action would be taken.

Still, her trepidation lingers.

When she asked the police about the possibility of backup copies, they told her to contact them if she ever encountered the images again. “At least if you report it to the police, there’s a record of it,” says Sarah.

She was later diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder by the Institute of Mental Health and still experiences flashbacks on occasion.

“I’m unwilling to do anything with a guy because I’m terrified. Will he take pictures of me when I’m not looking?” says Sarah. “This whole forgiveness part is something I’m still struggling with. I think it’s going to be a lifelong process.”

Violation of trust is a key repercussion of IBSA when exploitation takes on a digital form, reflects Sarah.

Among her Gen Z peers, it is not uncommon to hear of men pressuring their partners into sharing intimate pictures of themselves, telling them that it is to prevent them from resorting to pornography or looking at other girls, exploiting their jealousy and insecurity.

“When you’re in a relationship, you get swayed,” she says, adding that when most women send these pictures, they do not imagine their partners turning on them or violating their trust.

The worst fear of survivors is the permanent digital footprint of IBSA. Once online, an image or video can live forever in the dark corners of the internet, especially when takedowns are slow.

For Vayu (not his real name), IBSA was a deeply isolating experience because, as a gay man, he felt there was nobody he could turn to.

“I was embarrassed enough and I was scared of judgment,” he recalls. “I’m not out to my family, so they were out of the question in this scenario. And though I know now that my friends would have supported me, back then, I wasn’t sure.”

The incident took place in 2022, when a sexual partner posted a video of them on X, formerly known as Twitter. The video, in which his face is clearly visible, stayed online for more than 12 hours and racked up hundreds of views, despite Vayu pleading with the perpetrator to take it down.

The latter finally agreed only when Vayu threatened to “out” him to his family.

But the damage was already done. “People I know in real life saw it,” he says, and those included close friends.

He remains hurt by his experience, but never reported the incident to the authorities. “I wanted my perpetrator to suffer and feel some sort of consequence, but I can’t do anything without exposing myself in the process,” he says.

In his view, the issue of IBSA partly stems from how the internet has blurred the boundaries between consensually made pornography and non-consensual material. An increasingly voyeuristic digital culture means that leaked footage has become its own sub-genre of porn online, he laments, with a large audience of viewers who do not care how such content was created.

Worse, there are those who intentionally seek out non-consensually created content.

In 2021, an administrator of the SG Nasi Lemak Telegram group was jailed for nine weeks and fined $26,000 after the authorities found more than 11,000 obscene photos and videos on his devices, many of them non-consensually obtained or shared.

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) also adds a new dimension to this internet age crime, with the police launching an investigation into deepfake (AI-generated) nude photos of students at the Singapore Sports School in 2024.

To her horror, Janice (not her real name) discovered in 2021 that sexually explicit images and videos of her, taken by a former boyfriend before their break-up, had been spread online. Some were even being sold on Telegram and X as part of files of assorted women.

“They would organise these files by ‘year’ or ‘drops’, so in my ‘drop’, there was myself and about 10 other girls,” says the 25-year-old researcher. These files also identify the women by their Instagram handles.

Janice showed ST her correspondence with the police since 2021.

“For a few years, I would google my name with any combination of disgusting words they might use to identify me, like ‘xmm’ and ‘sg chiobu’, to find videos to send to investigation officers to take down,” she says. “I couldn’t leave my house without worrying about being recognised, or future employers finding these videos tagged to my name.”

Trying desperately to create distance between herself and the images that had spread like wildfire online without her consent, she resorted to self-harm, she says. “Even today, when I talk about it, I feel a physical reaction,” she adds.

Acquaintances continue to send her links to the offending material, which serve as constant reminders. “It gets easier to cope with, but it takes time, practice and support. And for me, the pain never went away,” she says.

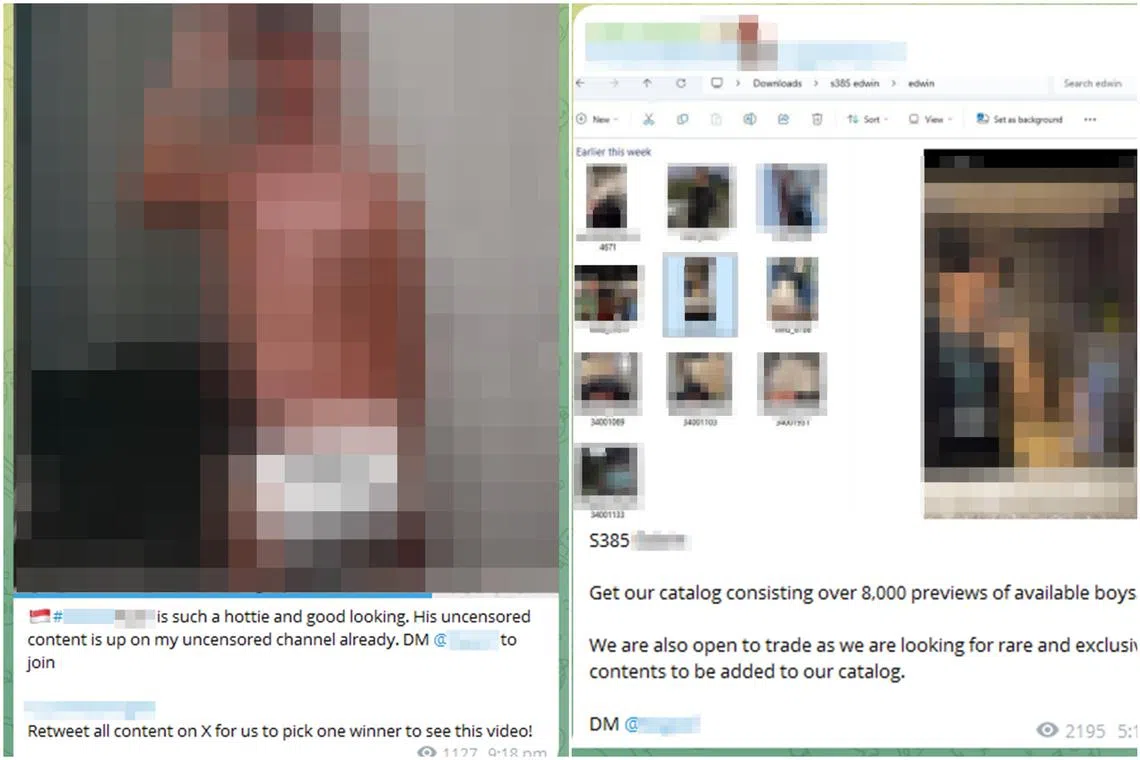

Even after the sentencing of the administrators behind the SG Nasi Lemak Telegram channel in 2021, The Straits Times reported in 2023 that similar communities, which offer sexually explicit material for a fee, have found ways to lurk in the shadows online.

Women are not the only targets.

ST found an active network of Telegram channels dedicated to non-consensually obtained material of men, with each channel drawing some 800 to 2,400 subscribers. The administrators of these channels sell access to a catalogue of sexually explicit material for up to $239 for two months of access.

“Similar to the concept of Netflix, our channels are constantly updated with uncensored content,” boasts one of the channel’s posts, referring to its over 8,000 pictures and videos up for sale, many of them tagged with a man’s name and social media handle.

A “baiting service” is also on offer for $199, where users pay channel administrators to catfish specific men. Catfishing entails using a fictional online persona with the intention to deceive, and is a common tactic in romance scams.

For survivors of IBSA, the ability to move past it is complicated by a pervasive societal attitude: the myth of the “perfect victim”. Many find themselves scrutinised not only for the violation they experienced, but also their perceived role in making it possible.

Nora explains the conflict she feels internally: “Even though you might say this was done against my will and without my consent, people automatically question, ‘What are these images? How did he even have them on his phone? And if you didn’t want this to happen, you shouldn’t have put yourself in this situation.’”

She adds: “I’ve internalised a lot of the shame. How could I have not known? How stupid am I that I didn’t suspect it?”

In her view, society has a cookie-cutter image of the kind of person who joins chat groups like SG Nasi Lemak – someone who is misogynistic, threatening and likely to leave lewd comments on women’s social media pages.

“You have a certain image in your mind of the kind of guy who’d do this kind of locker room talk, and my ex-partner was not like that at all,” she says of her former boyfriend, who presented himself as a progressive feminist.

Dr Michelle Ho, an assistant professor at the National University of Singapore (NUS), is the principal investigator on the Campus Sexual Misconduct in a Digital Age (Casmida) research project. She notes that in the SG Nasi Lemak case — in which many non-consensually obtained images, like upskirt photos, were shared on the Telegram channel — many of the perpetrators who were caught blamed the victims for uploading some of their content on social media in the first place.

Such victim-blaming narratives often discourage survivors from reporting cases, allowing perpetrators to act with impunity, she adds.

There is another misconception that IBSA is not as harmful as physical sexual violence, she notes. This is despite its potential to cause devastating and lingering psychological, social, reputational and even financial consequences for victims and survivors — in the form of harassment, job loss or legal troubles.

Nithiananthan says societal tendency to blame survivors — by questioning why they allowed the images to be taken or assuming they must have been careless — shifts the attention away from the perpetrators and discourages survivors from seeking help.

“Many assume that since non-physical sexual violence does not leave visible wounds, it must be less damaging. But the emotional and psychological toll can be just as severe, if not worse, due to the enduring and public nature of these violations,” she adds.

“Such images can resurface anywhere, countless times, and possibly live forever online. When society downplays these harms, it compounds survivors’ trauma, making them feel invalidated and isolated.”

For most victims, an immediate concern is how to remove the damaging material online as soon as possible, before it leaves a lasting digital footprint or spreads through messaging platforms.

As a trusted flagger of harmful content for major tech platforms such as TikTok and X, SheCares@SWCO, which assists the targets of online harms, focuses on getting this done.

Its chairperson Stefanie Yuen Thio tells ST that 45 per cent of posts that harm its clients are taken down within 24 hours of the centre flagging it to platforms. And nearly 70 per cent of these posts are taken down within 72 hours.

SheCares@SWCO, launched in 2023, was envisioned as a one-stop shop for everything a victim might need. “The one area that was completely unaddressed is online harms,” says Yuen, a joint managing partner at TSMP Law Corporation.

The Infocomm Media Development Authority’s 2024 online safety assessment report found that the social media platforms studied — which include TikTok and Instagram — took appropriate actions on around 50 per cent or less of the content that violated their community guidelines. Also, these social media platforms took an average of five days or more to act on user reports of such content.

Yuen notes that coming at online harms from the angle of a non-profit like hers can be useful. This is because many tech platforms do not want to be seen as bowing to government pressure, but do want to be viewed as working actively with the communities they operate in.

Beyond flagging harmful content, SheCares@SWCO also provides support in the form of counselling and free legal advice. It has an arrangement with the police to have officers take initial statements on-site at the centre in Waterloo Street, to ease the reporting process.

However, reporting the incident is only one part of a complex journey towards resolution.

“What is the purpose of lodging the report?” Charlotte (not her real name) remembers a police officer asking her after her brush with IBSA in 2021. “Is it to ensure there are no more videos?”

The questions seemed ludicrous to the then 20-year-old undergraduate, given how violating the experience felt: being filmed twice without her consent during sexual intercourse. When she discovered it, she deleted the videos she found on her former partner’s phone and reported the incident to the authorities — an experience that took an emotional toll on her.

She had to recount what she went through, and listen to a male officer repeat the details multiple times to other officers. Nine months later, the police informed her that the case would conclude with the perpetrator receiving a 12-month conditional warning.

“It felt really unsettling because it felt like I was putting my life on hold,” says Charlotte, now a model and tutor. “It was like I was waiting for the authorities to tell me whether what I felt was valid.”

Charlotte also reported the incident to her perpetrator’s university, which resulted in him receiving a two-year suspension, but he ended up dropping out of school of his own accord.

The trauma lingers. She now feels a sense of unease when she sees a camera phone pointed at her or whenever she uses the toilet in someone else’s home.

“I think the worst part is not dealing with the authorities or knowing that something had happened,” says Charlotte. “It is the fact that I couldn’t tell anybody who would understand my pain.”

For these reasons, she and other survivors have banded together to form The Moxie Collective (@themoxiecollective.sg on Instagram), an informal community which allows them to discuss their abuse in-person and find ways to move on together.

Casmida’s Dr Ho believes that harmful gendered norms are the root of the problem.

“At its essence, IBSA and other forms of sexual violence are about power. It’s about the fact that one person can enact power over the other,” she says.

“It’s also about not asking for consent and not respecting another person’s boundaries. IBSA exists within a culture that fails to recognise and respect each person’s right to sexual self-determination.”

Addressing it means challenging the increasingly normalised idea that sharing or consuming non-consensual images is in and of itself an act of harm, as well as promoting sex education on consent for both children and adults, some of whom may not have received such an education in the first place.

Dr Ho says that based on her team’s studies of campus sexual misconduct, IBSA starts younger than many would expect — as many are accessing technologies that can enable and expose them to IBSA as children and adolescents.

“For these ‘digital natives’, the boundaries between the physical and digital are increasingly blurred,” she adds. “This could be an issue if, for instance, they encounter digital sexual violence but are unable to understand or articulate this experience, and if so, how do we expect them to report it?”

Lynn (not her real name), a 26-year-old PhD student, found out in 2020 that her former boyfriend from secondary school had sent sexually explicit images of her, which she had shared with him privately, to a group chat of men that included their mutual friends as well as others she did not know.

This happened after their break-up, when they were 16, and she found out only four years later because he confessed it to her on a religious occasion when forgiveness is traditionally sought from friends and family.

Learning that these images had circulated without her knowledge among men whom she had considered friends left her humiliated and afraid. Fearful of her parents finding out, she chose not to report it to the authorities.

“The experience made me realise that guys will not call out bad behaviour on their own friends. It still baffles me to this day that I went four years oblivious to the fact that this happened – because no one told me,” Lynn says.

She adds: “Although I’ve mostly healed from it now, it’s really disappointing and, if anything, I just wished my friends would have done better, even at 16.”

In Aware’s survey of almost 800 people aged 16 to 25, it found that 12 per cent of respondents under 18 had engaged in some form of sexual activity with another person.

As such, improving Singapore’s sex education curriculum to better teach consent and sexual relations, beyond an abstinence-based message, is key, says Nithiananthan.

She adds that dedicated resources for victims of IBSA in Singapore which are publicly available and free remain insufficient.

However, she is heartened to see that on the regulatory front, change is happening. These include the introduction of the Online Safety (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act 2022, Code of Practice for Online Safety and Online Criminal Harms Act 2023.

Collectively, these new rules make social media platforms liable if they fail to protect users from online harms and allow the Government to order these platforms to take down egregious content.

Minister for Digital Development and Information Josephine Teo announced in March 2025 that a new dedicated agency, supporting victims of online harms by ordering the takedown of offensive material and providing information on the identity of perpetrators, will begin operations in 2026.

Says Nithiananthan: “These measures, taken together, are slowly strengthening recourse for survivors.”

However, she adds that this must be done in concert with tackling the root causes of IBSA, which are harmful norms and societal prejudice.

That most survivors stay in the shadows, afraid of sharing their story with others or reporting it to the authorities, is a sign that more change is necessary.

In her victim impact statement addressed to the perpetrator’s university, Charlotte wrote: “There is a paradox between me wanting to leave the filming behind and having to remember every detail for investigations. The incongruity between caring for my mental health and dealing with the due process.

“I break down randomly, unable to rationalise what is happening — I had been taken advantage of, but nothing is being done about it.”

In the statement, she addressed her perpetrator: “You cannot give me back my sleepless nights or my life before you filmed me. That said, your life is not over and you have decades ahead of you. You have a choice. You can do better.”

ALSO READ: Behind the OnlyFans porn boom: Allegations of rape, abuse and betrayal

This article was first published in The Straits Times. Permission required for reproduction.