This Brazilian artist creates artworks using materials like PB&J, ketchup and literal trash

It is thanks to his insatiable sense of curiosity that influential Brazilian artist, Vik Muniz, has been reaching out to others for the past three decades, repurposing a broad range of non-traditional materials to recreate canonical artworks that change the way people see things.

The 58-year-old dislikes working in his studio. To be productive, he needs to learn new things and meet people.

“I am not good at anything, except that I am very curious,” he confesses,

“I am the most curious person I know. I’m constantly trying to work with people who are experts in what they do, be they scientists, bioengineers, astrophysicists, psychologists, perfume makers or winemakers. It’s a risk when you work with people who have their own creative skills because they tend to be protective of what they do and know.”

Nonetheless, that has never stopped him and he relishes the opportunity for collaboration, saying, “As part of my practice, I work on several fronts, and one of these fronts consists of not just sharing my work with people when it’s done, but also sharing the work process. I find that [by sharing both] you don’t end up with something that you expect; you end up with something much bigger.”

So on one day, you might find Vik creating portraits with people scavenging in garbage dumps, or conspiring with the staff of the National Museum of Brazil to make works from the ashes of historically-significant archaeological and anthropological collections that had gone up in flames.

On another day, he’ll be working on a commission for the Vatican as they hold a synod for the Amazon reflecting on ecology, drawing with Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, or making art with a French luxury brand.

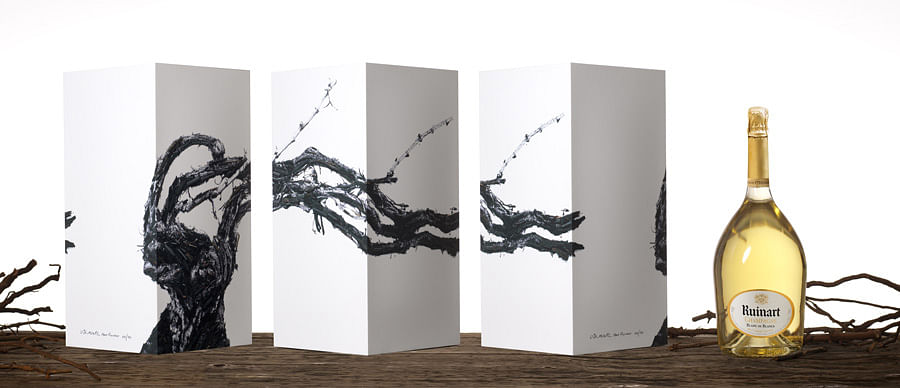

Recently tapped by Ruinart – the first established champagne house that has been partnering with artists since 1896 – to be its artist for 2019, he produced six photographs inspired by the winegrowers and vineyards and the challenges they face, thereby capturing the strong relationships between humans and nature.

“A lot of what I do as an artist has more to do with ignorance than knowledge,” he discloses.

“I am very drawn to the things that I don’t know. The idea of being open is very important, and I love to be part of projects like this, when you have a chance to do this.”

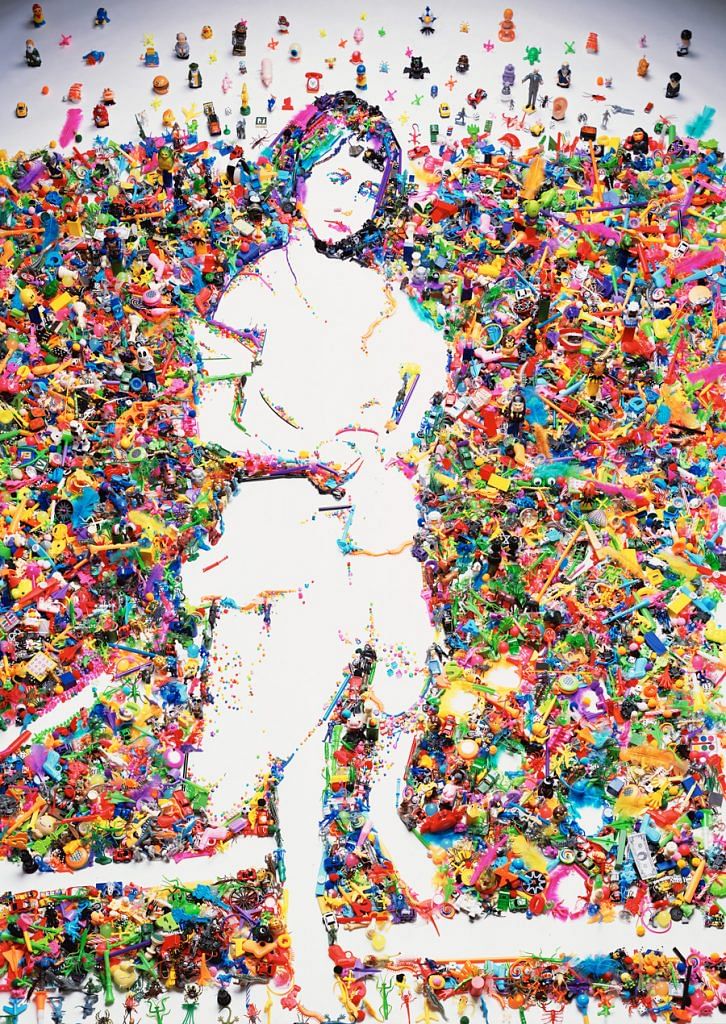

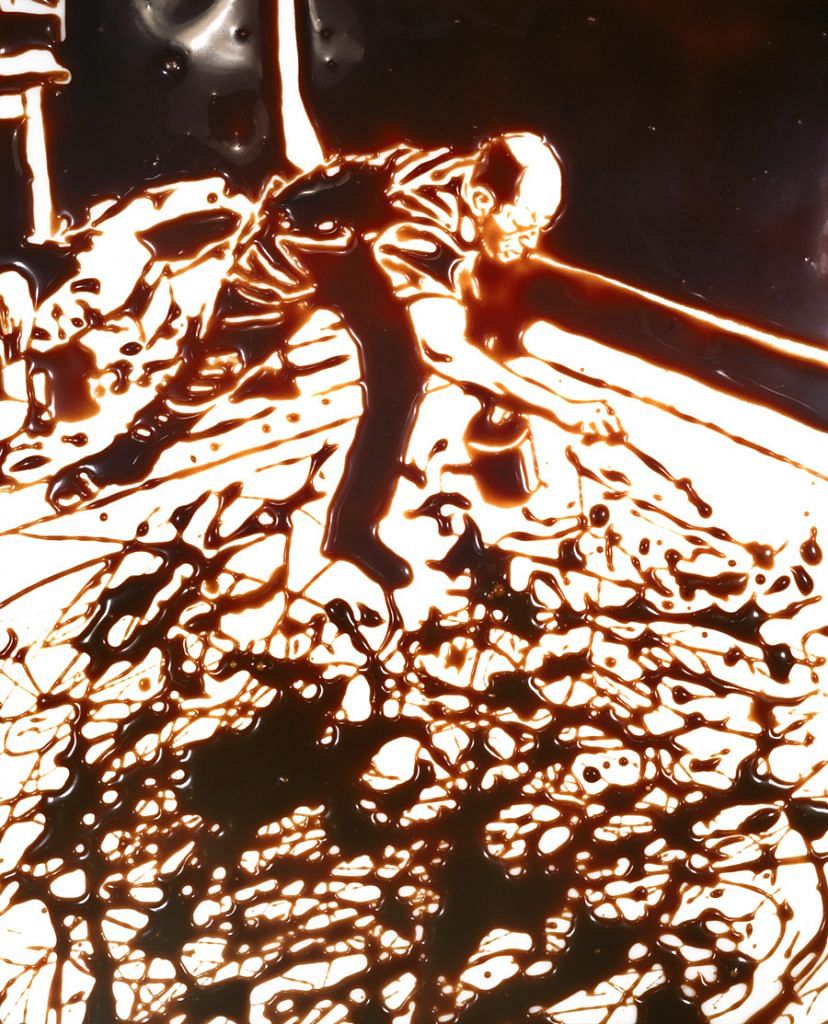

Vik is recognised for his artistic approach using unconventional materials like dust, linen thread, ketchup, cayenne pepper, spaghetti, caviar, fake blood, junk and flowers to form photographic images of famous art historical paintings. He was the artist who recreated Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper out of chocolate syrup, Andy Warhol’s Double Mona Lisa out of peanut butter and jelly, portraits of black Caribbean children out of white sugar, Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night out of pictures from magazines, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s Le Songeur out of yarn and likenesses of old Hollywood stars like Elizabeth Taylor out of diamonds.

Like an illusionist, he obliges viewers to do a double take – they believe they know what they’re looking at, only to realise moments later they’ve been deceived – thus exploring our collective memory in order to question it more effectively.

“I have worked with many materials for many years because each material forces me to adopt a different process,” Vik states, “I’m not interested in materials; I’m interested in processes. I tend to work with well-known images and very mundane materials, but the connection between the two gives a contemporaneity to it. It makes it something different. When you stop and think about an image, that’s art. That image has an effect.”

Growing up in a working class family, Vik recalls his childhood in Sao Paulo: “I was raised in a very poor household, so there was no art around. My parents worked all the time and it was during the military dictatorship, so I went to public schools. I never thought I would become an artist; it’s not something that somebody who comes from my background would plan. But one thing led to another, and I was always very interested in drawing. I was picked to represent my school in a kids’ contest when I was 13 or 14, and I won first prize. Then I had the chance to learn academic drawing for two years. Around that time, I started becoming interested not only in the idea of drawing but why people draw, how you get to see something that makes you think of reality in the picture.”

After working in advertising in Brazil redesigning billboards for greater legibility, he spent several months in Chicago in the ’80s learning English.

“When I was about to come back to Brazil, I went for a weekend to New York, and that changed everything,” Vik notes, “The weekend lasted 25 years. It was very cosmopolitan: I could get in touch with people with completely different life experiences than my own and learn a lot just by being there. There was so much culture around and it was so accessible; you didn’t have to look for it.”

Soon he started doing odd jobs: Working in the theatre, bartending, restoring artworks and designing children’s t-shirts.

Although never having attended art school, he began hanging out with the art crowd and thinking about how he could make a living as an artist.

He rented a studio, made and sold sculptures, and quickly had his first show at Stux Gallery in New York in 1989.

After seeing others photograph his pieces for promotional or documentation purposes, he eventually snapped his creations himself to ensure that the photos represented as closely as possible the way he had imagined his works to be before making them, and decided that those images, instead of the originals (which he discarded), would be his art.

The need for sharper and better pictures then compelled him to study photography, and today his pictures are prized for their technical virtuosity using large-format cameras.

Conveying the social and political slant of his work, Vik spent three years with the catadores (people rummaging through waste to find recyclable materials) to produce his Pictures of Garbage (2008) series made from thousands of objects found in the world’s biggest landfill in Rio de Janeiro, photographing trash pickers as figures from emblematic paintings that he reproduced, such as Woman Ironing by Picasso or The Death of Marat by Jacques-Louis David.

He also shot an award-winning documentary about the project called Waste Land to raise awareness about urban poverty and established an audiovisual school for youth in a Rio favela to help them to enter the job market.

When questioned about how his social activism (he’s a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador) impacts his art, Muniz replies, “I think my work does not necessarily speak about it. I am not really fond of art that starts with a political idea. Art should not be concerned about saving the world, but people, independent of what they do, should have such concerns. I have a range of interests as a person that I sometimes try to make part of my work, but normally they come diagonally and don’t inspire me to do things.”

“But I think everything you do has political value. In the case of Waste Land, it was about creativity and the practice of art making, something that makes you see things differently, and the effects of that, even for people who have no experience of art, where they change the way they look at themselves. For me, it was very instructive because I’m a mid-career artist and need to remind myself of the value of what I do or how it works. It actually encouraged me to do more. I try to make my work as open as possible so you don’t have to know about art history to be able to enjoy it.”

“When I have a museum retrospective, I want to communicate ideas with the director or curator and also to share something with the people who clean and care for it. I don’t have a specific audience because I try to do things that are very perceptual but also primitive. I deal with basic sensorial input and you don’t need any preconceived knowledge about what art is or what I do to be able to look at it,” he concludes.

This article was first published in Home & Decor.