Dead whale Jubi Lee found in Singapore tells tale of scientific discovery

SINGAPORE - It was bloated and smelled foul. Yet, in the rotting flesh and blood of the first sperm whale found in Singapore four years ago, researchers found a scientific payload.

In a paper published on April 5 in scientific journal PeerJ, scientists demystified the enigma of the female sperm whale nicknamed Jubi Lee, painting a clearer picture about what she ate and where she lived.

The team, led by mammal researcher Marcus Chua from the National University of Singapore's Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, made its discoveries literally piece by piece.

From the whale's DNA and with the aid of computer models, the scientists learnt that Jubi had likely hailed from a pod in the Indian Ocean, west of Singapore.

They also learnt from the content of the whale's stomach that, as with many others of her kind, Jubi favoured squid. But she had also eaten other marine organisms not commonly known to be the prey of sperm whales.

In her gut, scientists found the remains of pyrosomes, which are bioluminescent creatures that float freely in the sea.

These creatures look like "glowing giant fingers when alive", said Mr Chua. Sperm whales, excellent divers known to forage for food more than 2,000m underwater, probably hunted the pyrosomes because they were similar to glowing squids at depth, he said.

Jubi had also snacked on junk food - chunks of plastic were found in her gut. The amount of plastic found in her stomach was not large enough to kill her, Mr Chua said, but added that "elsewhere, plastic debris ingestion, especially masses of compacted plastic, has been noted to result in whale deaths by rupturing or blocking their guts".

Marine mammal biologist John Hildebrand, who was not involved in the study, told The Straits Times that whales are not likely to be picky eaters.

Said Dr Hildebrand, who is from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California: "Once in their mouths, they may not be too picky about what is swallowed, hence the ingestion of plastics."

The serendipitous discovery of the 10.6m-long sperm whale in Singapore waters provided scientists with a good chance to learn more about this charismatic marine mammal, which was the subject of Herman Melville's classic 1851 novel Moby Dick.

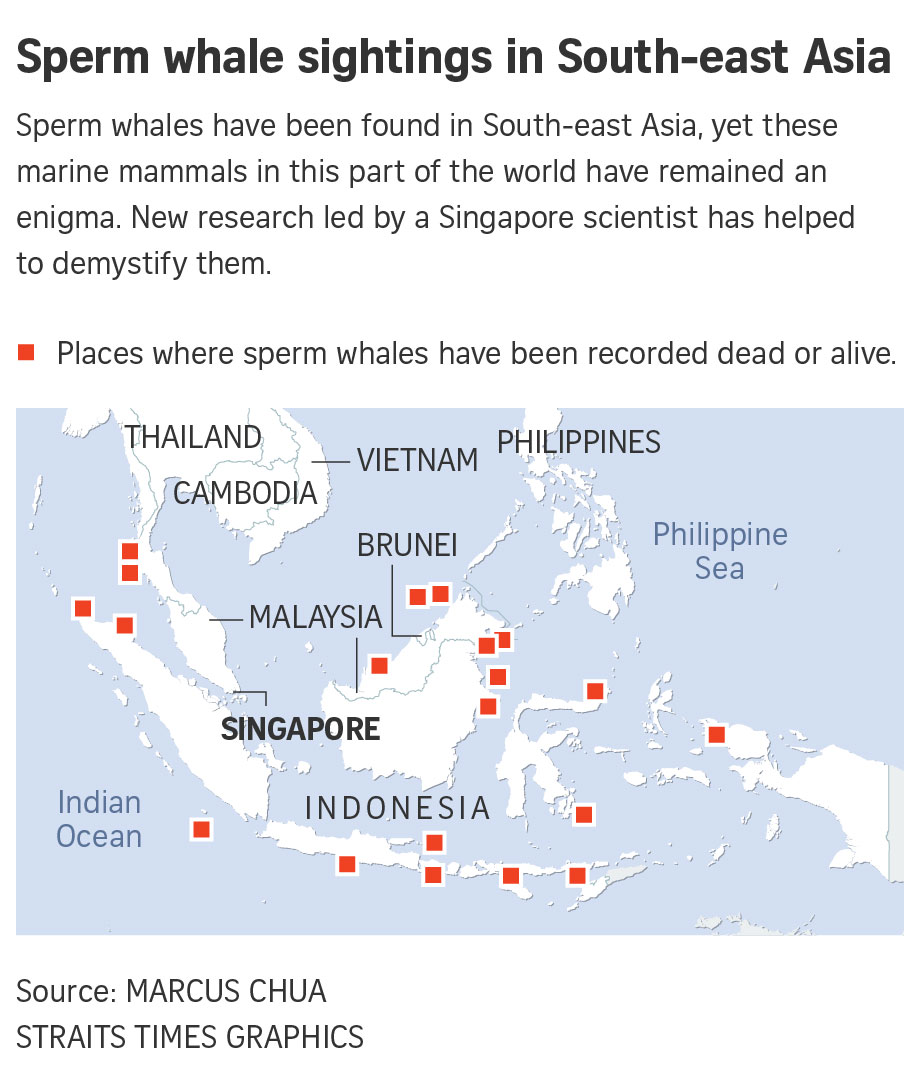

Said Mr Chua: "Even though sperm whales have been found in South-east Asia and there are numerous physical records of them in the Indo-West Pacific, little else is known about the biology of sperm whales in the region."

Jubi was found dead on July 10, 2015, floating off Jurong Island with a gash in her back. Her appearance during Singapore's golden jubilee year had led a museum staff member to give her the nickname Jubi Lee.

Scientists suspected that the whale, weighing an estimated 8 to 10 tonnes, died after a collision with a ship. Blood was still flowing from her wound when the scientists got to her, but Mr Chua said she had likely been dead at least a week.

Like a coroner assessing the time of death, he said the estimate was based on a combination of factors, such as the extent of the decomposition, the hot tropical conditions she was found in, and the salty medium in which she was suspended.

In comparison, roadkill salvaged in Singapore on the day of death usually do not smell bad, he said. Such carcasses are also usually not bloated.

Blood and gore aside, the fact that a sperm whale had been discovered in Singapore waters surprised many, including the scientists. The find was, after all, the first record of a sperm whale in the Republic.

"We wanted to know what happened to her, how she died, and how she got there," said Mr Chua.

And so began the tedious process of data collection.

Wielding steak knives and protected from whale spatter by masks, gloves, boots and overalls, researchers spent 10 days slicing through whale skin and blubber as tough as tyre, collecting skin samples and muscle tissue along the way.

Some questions, such as the likely cause of death, became apparent as the scientists processed the carcass. The deeper they dug, the more answers they got.

They hit the jackpot on Day Two of the process: The thin-walled stomach was uncovered and about 80 per cent of what was inside was salvaged.

Of this, 97 per cent comprised squid beaks - jaws of a squid made of protein and pigment that are hard to digest. Sperm whales usually vomit them out.

The squid beaks were stored in jars of ethanol until the defleshing work was completed.

Recalled Mr Chua: "They were opened and washed several months after we completed work on defleshing, and I was greeted by a tremendous pong and sensory-induced reminder of the work we did then."

Then came the question of where Jubi had come from.

Her DNA had shown that she came from a population of sperm whales that were widespread across the globe.

To narrow down the list of possible locations, scientists enlisted the help of technology. Hydrodynamic coastal models were used to simulate the flow of seasonal currents and tides around Singapore, which is located between the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

The results showed that the sperm whale drifted from the west of Singapore, probably the Indian Ocean, said Mr Chua.

"She probably did not come from other oceans, such as the Pacific Ocean, as this would suggest she drifted against the currents after she died."

The skeleton of Jubi can be viewed at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, where it is on display.

Mr Chua, who was involved in the preservation of the whale since she was discovered, said there were still more stories to tell.

For instance, her blubber could be analysed for toxins, and a more precise age estimate could be determined from her teeth.

Mr Stephen Beng, chairman of the marine conservation group of the Nature Society (Singapore), said the study could spur more research into whale ecology and raise awareness of the significance of whales and their plights.

Whales are not just charismatic creatures but they also help to support other marine life and help to remove carbon from the atmosphere, he said.

When whales die and their carcasses sink out of the water column, they take carbon to depths where it cannot de-gas out into the atmosphere.

The nutrients from their carcasses are also used to support life in the deep, where food is scarce.

"Dead whales washing up on our shore is literally the biggest sign that our ocean is in trouble," said Mr Beng.

Because marine mammals like whales have to surface to breathe, they are prone to collisions with ships.

"Diet-wise, plastic and other marine debris pollution are evident in all parts of the ocean and through food webs. It's everyone's responsibility to know the impact our little actions have on the ocean."

This article was first published in The Straits Times. Permission required for reproduction.

ALSO READ: Dead whale in Philippines had 40 kg of plastic in stomach