NGOs hopeful that regulating all migrant worker dormitories under single law will help workers in long run

SINGAPORE - A move on Tuesday to regulate 1,600 migrant worker dormitories here under a single law drew broad support from an industry association and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) serving foreign workers.

But dormitory operators most impacted by the expansion of the Foreign Employee Dormitories Act (Feda) are seeking greater clarity on new licensing conditions and how the law will be enforced.

Feda, which took effect in 2016, currently applies only to larger dorms that accommodate 1,000 or more workers.

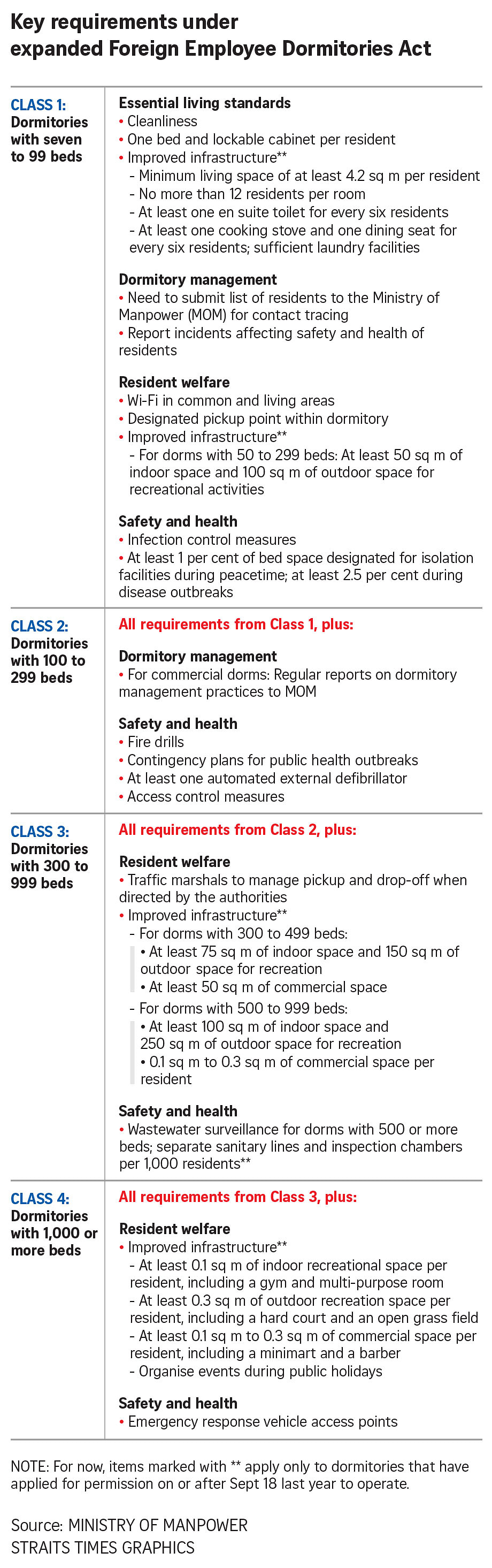

From April 1 next year, it will be extended to smaller dormitories with seven beds or more, with four licence classes and tiered requirements based on dormitory size.

For Mr Bernard Menon, executive director of the Migrant Workers' Centre (MWC), the move to expand Feda comes after years of advocacy.

Since the enactment of Feda, MWC had been asking the authorities why only dorms with 1,000 or more beds needed to be regulated under the law, he said.

Mr Menon noted that most of the complaints MWC receives about poor housing standards involve smaller operators, and that it was these smaller dorms that needed the most help during the Covid-19 pandemic.

"There was no unified code, so how do we professionalise the industry? How do we bring standards up across the board?" he asked.

"Once we have a baseline that is consistent throughout all dormitory operators, then you can look upwards... Otherwise, it is cowboy town, where everybody does their own thing."

Dormitory Association of Singapore Limited (DASL) council member Eugene Aw said the 1,200 factory-converted dormitories (FCDs) here will be the most impacted by the expansion of Feda.

But the changes at this time mainly pertain to improvements in dormitory management so the added costs are manageable, as they are administrative, said Mr Aw, whose firm RT Group manages five FCDs that currently house 200 to 300 workers each.

While improved living standards introduced for newly built dorms in September last year are part of the Feda licensing requirements, existing dorms do not need to upgrade their infrastructure just yet.

The Ministry of Manpower said on Tuesday that it is still in talks with dorm operators and employers about a transition plan.

Other FCD operators said they already have some of the new non-infrastructure-related requirements in place.

For instance, Wee Chwee Huat Scaffolding and Construction, which operates a dormitory in Woodlands that can hold 350 people, has a contingency plan for public health outbreaks, which will be a requirement for dormitories with more than 100 beds.

But the company's operations manager, Mr V. Manimaran, said he is unsure about other conditions he needs to adhere to, such as the requirement for dorms with 300 to 999 beds to deploy traffic marshals when directed by the authorities to do so.

"Are they looking for us to get a third party or a service provider to do this? That would mean a big cost for us," he said.

Dorm operators also want assurance that MOM will ensure everyone plays ball, said Mr Manimaran. "With over a thousand dormitories, will there be enough muscle to conduct enforcement?" he asked.

Mr Goh Boo Kui, contracts director at Unison Construction, which operates an FCD in Tuas that can house 315 workers, said he is more concerned about the infrastructural improvements that lie ahead. One such upgrade is the need for an en-suite toilet for every six dorm residents - something existing FCDs are largely not designed for.

Mr Goh said his company's dorm in Tuas may also not have the space for a big outdoor recreational area, which will be a requirement for dormitories of that size.

Mr Manimaran raised similar concerns, noting that physical changes to the building housing his company's dorm could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

For Mr Goh, the hope is for the Government to provide some subsidies and flexibility. If not, his firm may downsize its dormitory so it can meet the lower requirements being asked of smaller dorms.

The Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (Home) said it is hopeful that the expanded law will help migrant workers in the long run, but much will depend on the extent and spirit in which it is enforced.

The upcoming changes have already affected the availability of beds for workers, with some employers finding it hard to get housing for their employees, Home said.

According to the NGO, this has led to some workers being housed on-site or in ad-hoc locations with worse conditions.

The demand for beds in migrant worker dormitories has grown significantly with the easing of border restrictions and the gradual resumption of economic activity, said MOM.

Occupancy at the 30 commercial purpose-built dormitories (PBDs) here, and seven temporary quick-build dormitories (QBDs) set up during the pandemic, has bounced back to about 84 per cent of the maximum limit, MOM said in response to earlier queries from The Straits Times.

In comparison, the occupancy rate in PBDs was about 60 per cent last April, and 88 per cent in April 2020, before MOM made moves to reduce the density in worker dorms.

Home said: "We hope that MOM will closely monitor the well-being of workers, and make provisions for those who fall through the cracks, especially during the transition period."

This article was first published in The Straits Times. Permission required for reproduction.