How dams built by China starve the Mekong River Delta of vital sediment

AsiaOne has launched EarthOne, a new section dedicated to environmental issues — because we love the planet and we believe science. Find articles like this there.

Near the coast of Vietnam, the Mekong River splits into smaller branches and discharges into the ocean. This image shows a day of relatively clear water from the river.

However, under certain conditions, the water can carry tremendous amounts of rich, brown sediment for thousands of kilometres downstream.

This muddy goodness is the lifeblood of large parts of the river’s ecosystem as well as the livelihoods of those living on its banks.

Standing on the bank of the Mekong River, Tran Van Cung can see his rice farm wash away before his very eyes. The paddy’s edge is crumbling into the delta.

Just 15 years ago, Southeast Asia’s longest river carried some 143 million tonnes of sediment — as heavy as about 430 Empire State Buildings — through to the Mekong River Delta every year, dumping nutrients along riverbanks essential to keeping tens of thousands of farms like Cung’s intact and productive.

But as Chinese-built hydroelectric dams have mushroomed upriver, much of that sediment is being blocked, an analysis of satellite data by Germany-based aquatic remote sensing company EOMAP and Reuters shows.

The analysis reinforces an estimate by the Mekong River Commission, set up in 1995 by countries bordering the river, that in 2020 only about a third of those river-borne soils would reach the Vietnamese floodplains, and at the current rate of decline, less than five million tonnes of sediment will be reaching the delta each year by 2040.

Stretching nearly 5,000 kilometres from the Plateau of Tibet to the South China Sea, the Mekong is a farming and fishing lifeline for tens of millions as it swirls through China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia before reaching Vietnam.

“The river is not bringing sediment, the soil is salinised,” said Cung, 60, who has grown rice at his family’s 10-hectare farm for more than 40 years.

“Without sediment, we are done,” he said. His steadily diminishing harvest now brings in barely half of the 250 million dong (S$14,381) annually that he earned just a few years ago, and his two children and several neighbours have left the area to seek more stable and lucrative work elsewhere.

For decades, scientists and environmentalists have warned the impact of upstream dam projects jeopardises livelihoods in a region of some 18 million people and an annual rice market of $10.5 billion that is a major food source for up to 200 million people across Asia, according to WWF estimates, Reuters calculations and Vietnam’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

Worry shared by Lower Mekong nations has already led Cambodia to pause its plans for building two dams on the river, according to the Mekong Dam Monitor, an online platform that provides real-time data on dams and their environmental impact.

But in China and Laos, the dam-building goes on. Of seven new dams planned for construction in Laos, at least four are co-financed by Chinese companies, according to data from the Mekong Dam Monitor.

China’s foreign ministry said the country accounted for only a fifth of the total area of the Mekong basin and only 13.5 per cent of the water flowing out of the Mekong’s estuary, adding that there was already a “scientific consensus” on the overall impact of China’s upstream dams. The ministry did not address the dramatic decline in sediment levels or the role of Chinese dams in that decline.

The analysis conducted by EOMAP and Reuters tells a different story.

Using data derived from thousands of satellite images, EOMAP and Reuters analysed sediment levels around four major dams on the Mekong — two in China and two further downriver in Laos.

The analysis showed the presence of each dam drastically reduced the sediment that should have otherwise flowed through the river at those locations — by an average of 81 per cent of the sediment load flowing across the four dams.

“The dams are trapping sediment… each one traps a certain amount, so there isn’t enough reaching the floodplains,” said Marc Goichot, a river specialist at the WWF in Vietnam, who was not involved in the analysis but reviewed the results.

“Sediment and deltas should be able to regenerate and rebuild themselves,” he said. “But the pace at which the natural balance is being forced to change in the Mekong is too fast for the sediment to keep up.”

The Mekong river begins 5,160 metres above sea level in China, where it is known as the Lancang.

The Mekong River Basin is divided into upper and lower sections. The upper section cuts through rugged terrain with most of the flow coming from snow melting in the Plateau of Tibet. It makes up around 24% of the total basin area, yet around half of the total sediment load originates there.

A string of dams is scheduled to be built in this far north stretch of the river, close to the source.

Downstream the Mekong runs alongside two other prominent rivers, the Salween and Yangtze. These rivers flow through a designated Unesco World Heritage Site, the Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, a biodiversity hotspot in China. However, this area is not immune to the proposed dam infrastructure.

The Wunonglong dam — the most northerly operational dam — went online in 2018. China has 10 additional dams that are operational, including the first hydropower plant to be built on the Mekong in 1995.

China has eight additional projects, either proposed or already under construction, and Chinese companies are helping co-finance additional dams in Laos.

The value of the energy from the hydropower dams in the Upper Mekong River Basin is estimated by the Mekong River Commission at $4 billion per year, yet this energy comes with costs.

The hydropower stations in China hold back precious sediment and water from the 65 million people living in the Lower Mekong River Basin, many who rely on the river and its floodplains for their livelihood.

The basin widens as it transitions into the Lower Mekong River Basin, south of the China-Laos border. Here tributaries bring in a large influx of water, making up for most of the total water flow for the Mekong river.

Hundreds more dams are located on tributaries feeding into the Mekong.

Dams are not the only activity affecting sediment moving downstream. Sand mining from the riverbed and the increase in deforestation to make way for expansion of agricultural land are varying the amount of sediment that flows into the Mekong.

Towards the Mekong Delta sits Tonle Sap Lake, connected via the Tonle Sap River. It is known as the “beating heart of the Mekong”. As the world’s largest inland fishery it is a vital part of the region’s economy and a valuable source of protein for the millions of people in the area.

Each year during the wet season, the direction of the Tonle Sap River reverses. This fosters sediment exchange and fish movement between the Mekong River and Tonle Sap Lake. Hydropower stations blocking water and sediment upstream put this critical exchange and flow reversal at risk.

Any sediment that does make it all the way downstream spills into the South China Sea. With a length of 4,900 kilometres, the Mekong is the longest river in Southeast Asia and the 12th longest in the world. Studies estimate that 96% of the sediment load will be trapped if all dams proposed in the Mekong Basin are developed.

Farmers in the Vietnamese Mekong River Delta region were not prepared for the speed at which their landscape — and fortunes — have changed.

The area under rice farming has shrunk by 5per cent in the last five years alone, with many farmers forced to adopt shrimp farming in salty seawater as an alternative, and incomes in this once-booming region are now among Vietnam’s lowest, even as the national economy grows at a projected eight per cent for 2022.

Amid uncertainty over future prospects, the Mekong River Delta region has seen more outward migration than any other Vietnamese region since 2009, according to the country’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

The Mekong River Commission estimated in 2018 that total sediment flow by now would be around 47 million tonnes per year. In fact, it could be far lower —estimated at just 32 million tonnes per year, according to several scientific studies from the last decade including one published in July 2021 in the journal Nature Communications.

“In the past three or four years there has been a wake-up call about sediment,” said the head of the commission, Anoulak Kittikhoun. “We definitely cannot return to sediment levels seen in the past. We need to preserve what we have.”

Meanwhile China, eager to boost its renewable energy capacity to reduce its reliance on coal, has already built at least 95 hydroelectric dams on tributaries flowing into the Mekong, called the Lancang in China.

Another 11 dams have gone up since 1995 on the main river itself in China — including five mega-dams each standing more than 100 metres tall — while China has helped to build two in Laos.

Dozens more are planned in China. State-owned Huaneng Lancang River Hydropower, tasked with developing the river’s resources, aims to double the network’s 21.3 gigawatt capacity by 2025, its chairman Yuan Xianghua told Reuters.

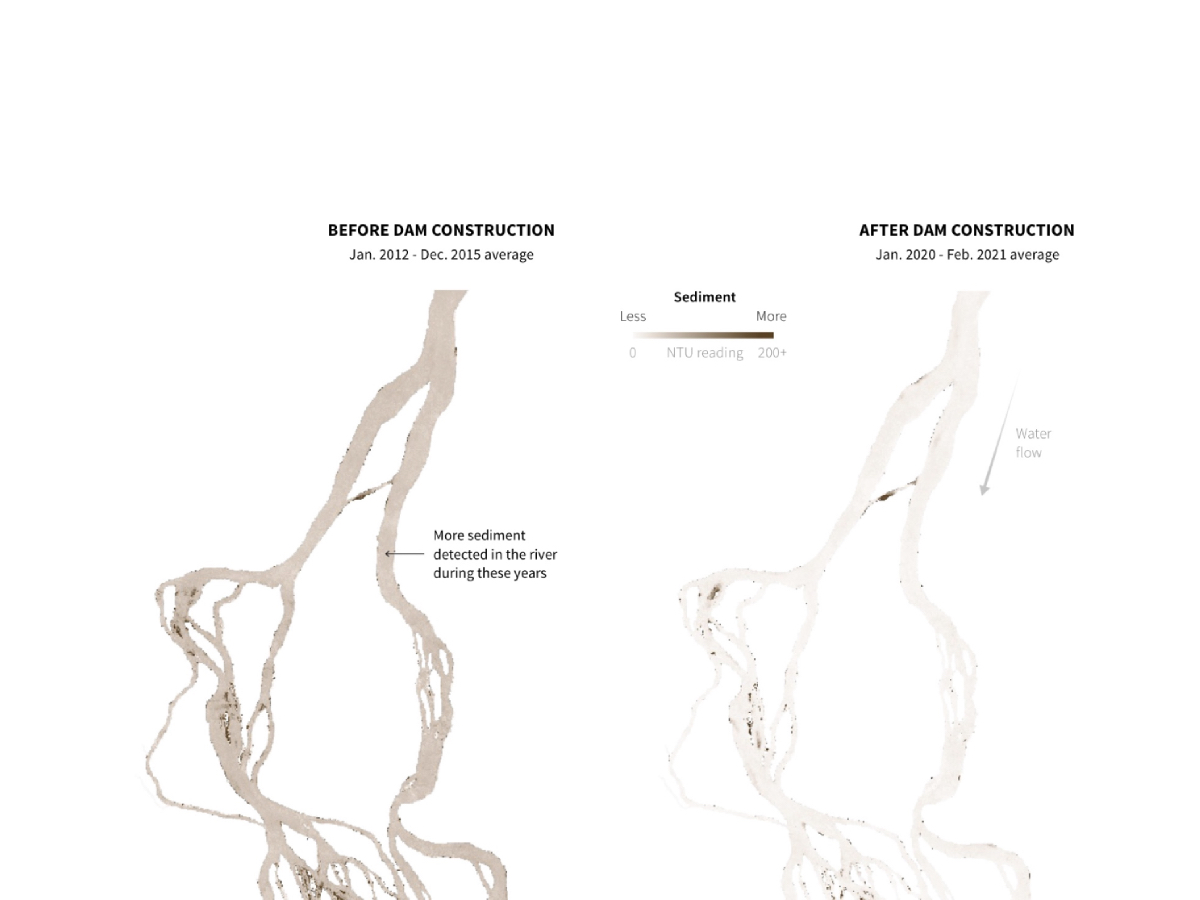

The analysis by EOMAP and Reuters of satellite images taken over three decades around four major dams in China and Laos found evidence that the dams are reducing sediment flow drastically.

The analysis relied on measurements of turbidity depicted in the images — the amount of light scattered by solid particles suspended in water — as a proxy for sediment levels.

Sediment clouds the water as it is carried along by the current: the muddier the water, the higher the turbidity and the more sediment it is likely carrying.

EOMAP used the same approach to gauge sediment flows in the Elbe River in 2010 and sediment loads in hydropower reservoirs in Switzerland and Albania in 2021. Its findings on those waterways in Europe matched ground observations.

The satellite images for the Mekong analysis date back to the 1990s, which “allows us to calculate turbidity levels before many of the dams were built,” said EOMAP data analyst Philipp Bauer.

After discarding images obscured by cloud cover or pollution, the team was left with 1,500 images depicting the turbidity around two dams in China and two in Laos. Scientists not involved in conducting the analysis agreed that the findings made clear that the dams were a key culprit behind the delta’s sediment loss.

“Mainstream dams catch everything,” said economist Brian Eyler at the Stimson Center, which runs the Mekong Dam Monitor. “China’s got 11 on the mainstream, plus other countries, so all these are working together to reduce sediment load.”

For example, before China built its fourth-largest dam at Nuozhadu in Yunnan province, the water’s turbidity measure in 2004 was an average of 125.61 so-called ‘nephelometric turbidity units’, or NTUs, according to EOMAP satellite data.

After the dam was completed in 2012, average turbidity at the same spot plummeted 98 per cent to just 2.38 NTUs — clear enough to meet the World Health Organization’s classification for drinking water.

The Xayaburi and Don Sahong dams in Laos are the most recent to come online, with Xayaburi being the largest on the entire Mekong River. Both structures faced years of opposition from environmental activists.

The average turbidity before China constructed the Xayaburi dam was 101.51 NTUs. After the dam came online in 2019, turbidity tumbled 95 per cent to an average of 5.16 NTUs.

And on Laos’ southern border with Cambodia, turbidity fell about 42 per cent to 42.39 NTUs after the Don Sahong dam started up in 2019. The graphic below shows the stark decrease in observed sediment levels across the entire stretch of river.

Reuters asked both the Chinese and Laotian governments about the impact of their dams and their plans for building more. China’s foreign ministry did not respond to questions about its existing and planned dams or their impact on sediment levels, while the Laotian government did not respond to requests for comment.

Governments of other countries through which the Mekong flows also did not respond to requests for comment.

At Cung’s rice farm in Vietnam, riverbank seedlings have little time to take root before they fall into the water as the banks give way.

Even though the farm is about 430 kilometres (270 miles) from the nearest upstream dam — and roughly 1,400 kilometres from the Chinese border — the turbidity has changed here too, dropping about 15 per cent in the last 20 years, to about 61 NTUs on average today, according to the analysis by EOMAP and Reuters.

Downriver countries affected by the dwindling sediment have lobbied unsuccessfully for China to share not just details of its domestic dam-building plans, but also its data on sediment flows. Beijing shares data only about the water levels and flow rates from its mainstream dams.

Last year, the Mekong River Commission launched its own joint study with China looking at the dams’ impacts on the entire basin, but the results won’t be known until 2024 at the earliest.

But while the commission has raised concerns about sediment depletion, “We have not had a serious conversation [with China] about sediment yet,” said commission chief Kittikhoun. That’s because “water flow is a priority. Working with China, you have to take it one step at a time.”

Sitting cross-legged by the river, Cung said he and his peers have struggled to find information about how to adapt to the changes wrought by dams, changes driving many to leave.

"It's not an easy decision to make but sometimes quitting is the only economic choice that makes sense," Cung said.

ALSO READ: Mekong villagers land heaviest ever freshwater fish

Source: Reuters