'We're a first party of the restaurant': Oddle founder Jonathan Lim wants to help eateries help themselves

When dim sum restaurant Swee Choon turned to Jonathan Lim in January 2020 to see how it could improve its e-shop, he noticed something.

Swee Choon was selling its siew mai (pork and shrimp dumplings) and other offerings by the piece. If a customer wanted to buy three dumplings, he would have to click thrice.

“The thing about buying online is every click is friction,” says the co-founder and CEO of The Oddle Company. “You don’t really want too many clicks before a person checks out.”

He suggested that Swee Choon sell its siew mai and other dim sum in bundles of four or six pieces.

It should also create “party sets” featuring a mix of its signature dim sum for different group sizes, ranging from four to 10 people.

Such bundled meals would make it more convenient for families. Customers were also more likely to complete their orders if the process was fast and simple.

Swee Choon would see an increase in earnings as order baskets would be bigger, he promised.

As Mr Lim, 37, is relating this to me, I have an “aha” moment.

Stuck at home during the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, online food delivery services like Oddle saved me from the tedium of home-cooked food. They also provided pockets of excitement and happiness during those dark days as I awaited deliveries from favourite restaurants I could no longer visit, or new eateries I had never tried.

I remember being impressed by the convenience of “set” meals featuring a restaurant’s best-of dishes and ordered my fair share of them. Now I know the thinking behind it.

Oddle was one of the companies that benefited from the pandemic. “It’s a bit fortunate for us that the pandemic happened,” Mr Lim says.

Realising how this could sound, he adds: “I don’t mean it that way. But we were lucky. We saw the wave very early on and we became a household brand in a very short period of time.”

It wasn’t just sheer luck, though. He notes: “This was six to seven years in the making.”

He and two friends founded Oddle in 2014, early days when there were few other players, to provide a delivery platform for restaurants. The company has since expanded to providing e-marketing services and payment terminals.

It now works with 1,500 restaurants in Singapore. It is also in Hong Kong, Malaysia and Taiwan, working with 5,500 restaurants in those other markets.

In October last year, Mr Lim was Ernst & Young’s EY Entrepreneur of the Year in the food and beverage solutions category. The overall Entrepreneur of the Year award in Singapore went to founder and CEO of Doctor Anywhere Lim Wai Mun.

Lunch with the Oddle founder is at Kulto, a Spanish restaurant in trendy and buzzy Amoy Street in the business district.

The area is packed with an office crowd and all the tables at Kulto are filled. We have to shout above the din to hear each other speak. The pandemic seems a lifetime ago.

“I know the good food here,” he says, settling into his chair.

I ask him to order for us.

“Any dietary restrictions?” he asks.

I tell him I’m fine with everything except lamb.

He confers with the waiter and chooses dishes he remembers enjoying: jamon iberico bellota, salmon tartare, roasted pumpkin, iberico pork rib-eye, and paella. They are all delicious.

Are you a foodie, I ask.

“Well, I have to be, right? It’s part of the job,” he says. His manner is straightforward and he speaks eloquently, even as he professes to being uncomfortable in the limelight.

He had always wanted to start a business, he tells me.

He is the youngest of four siblings and grew up in Pasir Panjang and later Jurong. One brother now works in the Singapore Armed Forces, another brother is in banking, and his sister owns a travel agency.

His father had a factory that made building construction material, and the business faced hard times during the 1997 financial crisis.

He attended Qifa Primary School, followed by River Valley High and St Andrew’s Junior College.

He wasn’t a bad student but wasn’t focused on studying. When he entered the National University of Singapore (NUS) to study mechanical engineering, he decided to buck up. “I just figured that I probably should study once in my life, right?”

He was the third sibling to study mechanical engineering, and he remembers his father telling him: “I just want you to know, in case this is lingering in your mind, that my business is a sunset business. Don’t even think about helping me or turning it around because you should chase your own dreams.”

Says Mr Lim: “I remember that conversation. My dad is like an Asian parent, he doesn’t talk much, and that conversation struck me.”

He stuck to his engineering course but was itching to try his hand at business.

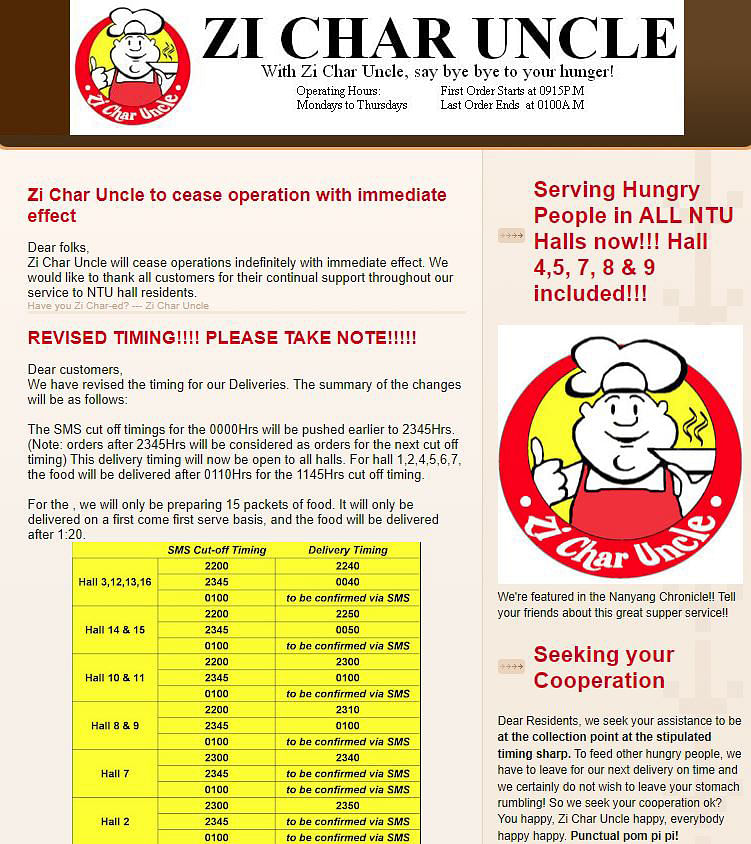

Together with a friend, he started a food delivery service on Blogspot called Zi Char Uncle with the tagline “With Zi Char Uncle, say bye bye to your hunger”. It targeted students staying in hostels at the remotely located Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

Taking a loan from his sister, he bought a van to carry out deliveries. Orders were made via SMS from a menu that included seafood horfun, chicken wings and Hokkien mee priced from $4 to $4.50. He also sold canned drinks from his van, at $1 each.

“My relationship with food started back then,” he reminisces. “It was not serious money but it was so fun. I couldn’t sleep. Every night, I was thinking about how to optimise the business.”

His friend thought he was taking it too seriously, he remembers with a laugh. “He said, ‘Dude, we’re here to study, we’re not here to run a business.’”

The venture lasted three semesters.

At NUS, he also signed up for the NUS Overseas College (NOC) entrepreneurship programme, for which he had a study-work attachment in Silicon Valley in the United States.

He was assigned to a company that dealt with fibre optic cable infrastructure, a complex field which he found fascinating.

“I had one goal, which was to get the company to offer me a full-time job, and then I would reject it so that I could tell my mum, ‘It’s not because I cannot find a job, it’s because I prefer to do my own thing,’” he laughs.

And did he get an offer? He says he did, after mapping out a proposal which could save the company “millions” by trimming infrastructure redundancy. He turned down the job and went home because “I’m a Singapore son”.

“The programme exposed me to the fact that people that made it in Silicon Valley, they are normal people like us, and we have a fair shot at success,” he adds.

One of his favourite restaurants in the US was Pluto’s, which served build-your-own salads and steaks.

After he graduated in 2011, he opened The Lawn Cafe at the Biopolis biomedical hub in Buona Vista with his own money and help from an investor. It specialised in salads and grills.

This might be common fare nowadays, but he reminds me it wasn’t back then in Singapore. “There was no concept of a protein diet, no salad-based foods.”

A second outlet opened at AXA Tower later, but closed because of high rentals.

At that time, food delivery was largely limited to pizza and fast food, where customers would place their orders by phone. Restaurants hardly did deliveries.

Those which did took orders through the phone, e-mail or SMS. “You had to write the order down on a piece of paper, remember the customer’s order, hope that he transfers you the money, or hope that he is a real person when you show up and that he passes you the money. You had to find your own logistics.”

He considered installing a more sophisticated system like what the fast-food players used. But it would have cost $300,000.

In 2012, delivery platform foodpanda entered the scene. But it was too expensive for a restaurant like his, he says.

“Every order, they’d take about 30 to 35 per cent, which was super expensive when my corporate orders were in the range of $300 to $400,” Mr Lim recalls.

He wondered why restaurants didn’t have a platform where they could “own their own customers” and serve them directly.

“Hotels have their own booking system, right? You can go to Marriott and book your own room. But there was no such thing for restaurants. It was only McDonald’s, KFC and Pizza Hut which had delivery.”

In 2013, he decided to build a platform that the restaurant industry could use.

Oddle was launched the next year with two partners – Mr Alan Goh, who is now chief revenue officer, and Mr Pua Yong Xiang, who is chief technology officer. Mr Goh had started out at food portal HungryGoWhere, and Mr Pua’s background is in financial services.

The co-founders bootstrapped their start-up through angel investors and friends. The name is a play on “order”.

The platform was built in-house, and the founders went round to restaurants to persuade them to sign up. Oddle takes a 10 per cent cut from each delivery and takeaway order. Deliveries are outsourced to transport providers – it currently works with Lalamove, GrabExpress and pandago.

Unlike other platforms which deliver within a limited radius, Oddle delivers islandwide, though with higher delivery fees.

The company later offered digital marketing services to restaurants. By 2019, it was working with about 1,000 food merchants. For the financial year April 2019 to March 2020, it had revenues of $2.7 million.

When Covid-19 hit and dining in was banned, more restaurants signed up to use Oddle’s delivery platform.

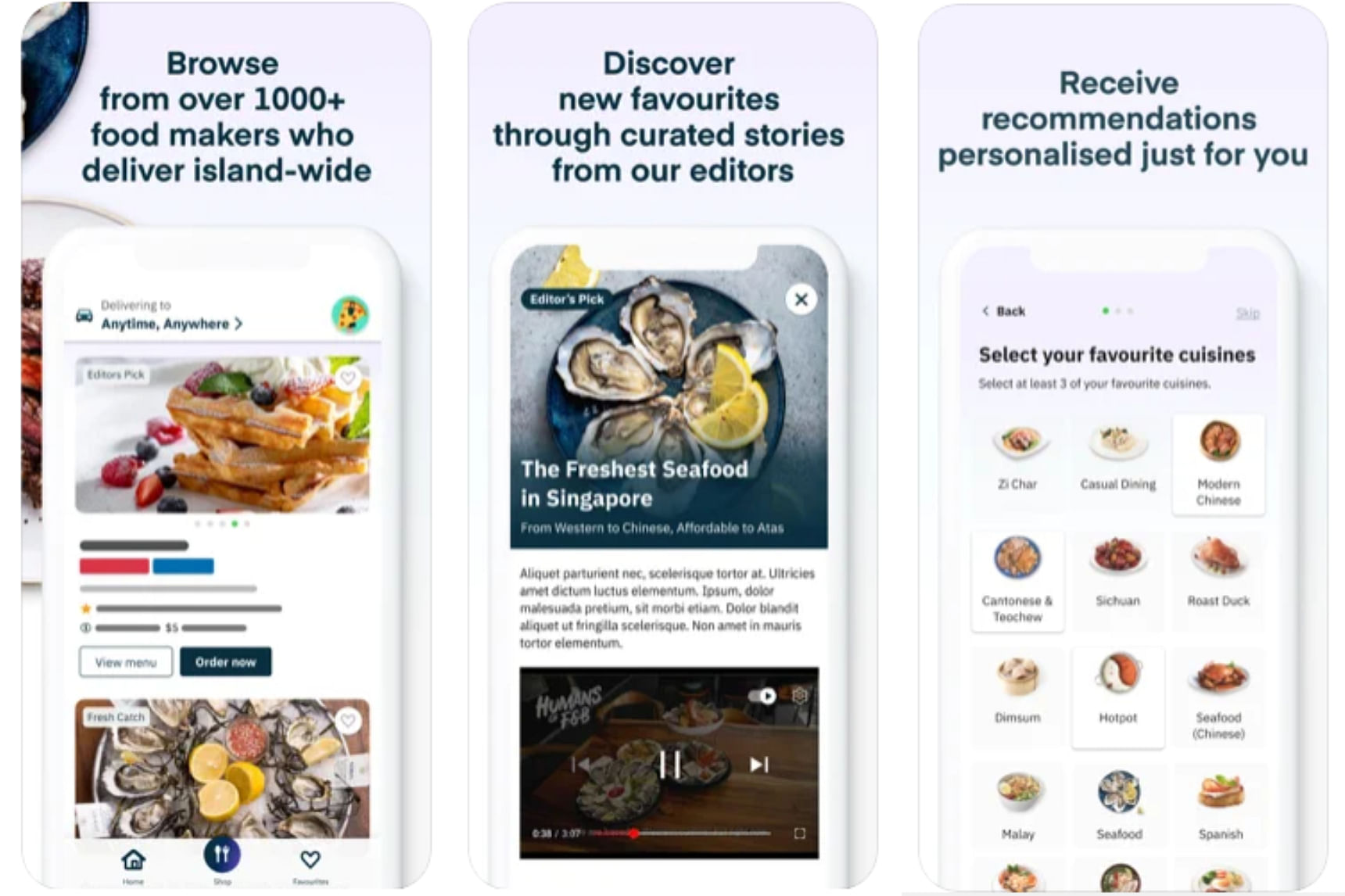

The company created Oddle Eats, a directory of the eateries on its platform. “We do not charge anything on top of our existing B2B solutions, so Oddle Eats does not have revenue on its own,” he says.

Beyond delivery and takeaway, it went into reservations and QR ordering, which come at no charge to the restaurants.

It also started helping restaurants get sponsorships from banks, entered the payment terminal space – it makes a margin from each transaction made through its terminals – and facilitated financing for merchants that needed loans. It plans to charge a nominal fee for engagement through SMSes and e-mail, such as reminders on reservations.

For financial year April 2021 to March 2022, revenues rose to $24.5 million. It has so far also raised over US$12 million from venture capital funds, institutions and individual investors.

A large part of what Oddle does is to help restaurants understand the profile of their customers, he says. The Oddle platform is basically the restaurant’s website. “We are not a third party, we are a first party of the restaurant” is how he puts it.

Customer data that Oddle is able to collect from the platform is available to the restaurant. It can get information like sales, visitors and orders by outlets, over time, and by days, and how many customers who visit their page actually complete an order.

“In a digital world, it’s super important for a restaurant to know who their best customers are,” he maintains.

While its delivery business is profitable, the overall business isn’t yet because of its regional expansion. The company has about 160 employees and is now expanding its services into the dining-in space.

Competition is strong. On the delivery front, it has to compete with the likes of Grab and foodpanda. In the reservations space, there are Chope, Quandoo, Inline and SevenRooms, and in QR ordering there are Aigens and TabSquare.

“While we have various solutions from online to offline, we don’t engage all our partners to use all our solutions. Different restaurants would require different solutions from us.”

For example, more than 430 merchants have come on board in the six months since it launched its reservations service, he says. On the other hand, fast casual restaurants do not need reservations but would need terminals, and about 200 merchants have signed up for its terminals so far.

The industry is heavily reliant on people and he has had his fair share of strange encounters, like a delivery driver who decided to help himself to the bubble tea that came with a meal. “He passed the food to the customer with the bubble tea straw in his mouth. He was drinking the customer’s bubble tea.”

As someone whose world revolves around food (he has made 200 orders over the last two years), does he have any favourite restaurants to share?

He gets this question a lot, he says. “I don’t have a favourite restaurant, but I have a favourite restaurant of the moment,” he says diplomatically.

Right now, it is Chef Kang’s, a small, acclaimed Cantonese eatery in Mackenzie Road. “He’s a Singaporean brand and I really think that his food needs to be shared with the world.”

He relents and shares more names. He loves zi char and keeps returning to Keng Eng Kee Seafood, or Kek, a zi char stall in Alexandra.

“I like Kulto quite a bit, which is why I recommended this,” he says of our lunch venue. For their wedding anniversary, he and his wife went to Whitegrass Restaurant at Chijmes. She does compliance in a liquor company and they have a three-year-old daughter.

87 Amoy Street

Total (with tax): $211.85

As we wrap up the meal, I ask him for the most rewarding aspect of his business.

“If you asked me the same question three years ago, I would probably give a very different answer,” he reflects.

“But what changed over the last two years is we started seeing our work making an impact on the people in the industry. We know that we have saved a lot of jobs because we managed to help them reach out to their customers beyond the four walls of the restaurant, and I think that motivates us a lot to do more,” he says.

“What gets me excited every day is that we have a chance to redefine the industry in a meaningful way.”

It is also redefining how customers eat.

While writing this piece, I had a craving for a pita sandwich from an Israeli restaurant downtown. Only Oddle would deliver to my office 10km away, and it made my day.

ALSO READ: Foodpanda, Deliveroo, GrabFood, Oddle Eats: Which is the best food delivery service?

This article was first published in The Straits Times. Permission required for reproduction.